In Canada and the US, lawyers are not subject to anti-money laundering reporting obligations like they are in most other countries. One of the most frequent reasons given for this by lawyers is that to require us to report certain financial transactions to a financial intelligence unit is inconsistent with, and would undermine, legal privilege.

However, privilege does not cover advice obtained from lawyers for a criminal or fraudulent purpose, or in cases where the advice is sought that has nothing to do with legal advice, such as asking a lawyer for business advice, valuation advice or when using trust accounts as a deposit-taking institution (depositing funds in a trust account for banking purposes to avoid using a bank and yes, this happens but is inconsistent with the rules governing lawyers). It also does not apply for non-clients, although the lawyer should tell a person attempting to give him or her unsolicited legal details that may be confidential that they do not want to receive the communication and that no privilege attaches as far as the lawyer is concerned.

In anti-money laundering law, the key reporting obligation is the one that arises in cases where there are reasonable grounds to suspect that a financial transaction is associated with a money laundering or terrorist financing offence. In respect of the latter, all lawyers must already report terrorist financing to the federal government, and freeze terrorist funds.

Law of Privilege

Let’s look at privilege. The application of privilege can be straight forward in most cases, especially in Canada.

First of all, the privilege belongs to the client and not to the lawyer or the law firm. Hence, a client can waive privilege expressly or by accident by disclosing otherwise privileged information to a third party (a non-lawyer).

In essence, the law of privilege is that communications received by a lawyer or advice given that is within the ordinary scope of professional engagement is protected and its disclosure cannot be compelled in any court of law or equity. The reason for the rule is that privilege is necessary for the administration of justice because clients have to be able to confide in experts in jurisprudence in respect of their rights and obligations.

However, any communication or advice that is criminal or intended to further a criminal purpose injures the interests of justice and the administration of justice and is not protected by privilege. In fact, such a communication or advice is not even within the scope of “professional employment” of a lawyer and cannot be covered by privilege. No lawyer can be, or is, in the business of furthering criminality. If a client obtains advice from a lawyer by fraud or deception (eg., does not tell the lawyer the real reason for the advice) and it later emerges that the advice was for a criminal or fraudulent purpose, the advice is not protected by privilege.

Another way of saying it is that while there is privilege protecting communications between a lawyer and client, it disappears if the relationship is abused. A client who consults a lawyer for advice for the commission of fraud or for criminality “will get no help from the law. He must let the truth be told” (US Supreme Court Justice Cordozo). On the issue of confidentiality, Canada’s Supreme Court has held that “communication made in order to facilitate the commission of a crime or fraud will not be confidential, regardless of whether or not the lawyer is acting in good faith. The US Supreme Court has held that advice rendered by lawyers in good faith, if used to accomplish an unlawful purpose leaves the communication unprotected by privilege and in essence, a lawyer’s ignorance of a client’s misconduct does not protect the client from his or her wrongdoing.

In a nutshell, for anti-money laundering reporting purposes (our topic here), if the communication or advice is in respect of criminality or fraud by the client, whether or not the lawyer is aware of it, no privilege attaches to the advice or communication. So, if the lawyer suspects that a financial transaction involves money laundering, that appears to fall within the exception to privilege and ergo, privilege becomes irrelevant since no privilege would attach to advice given in furtherance of a money laundering financial transaction.

Sample Situations where Privilege May or May Not Apply

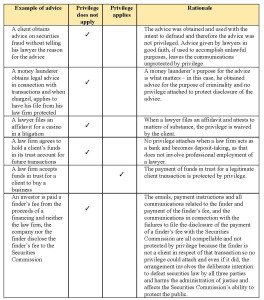

Here is a handy chart of real life situations in corporate, fraud and money laundering law that have arisen (click on the charts below for a larger view) where you can see when privilege does and does not apply. Certain conduct can erode privilege, for example, sharing advice with investment bankers, accountants. The difference in the chart between cases when privilege does not apply are: where it applied but was waived (by an affidavit describing advice, for example); or where it never applied because the advice was for criminal activities.

Privilege Law Tips

Privilege protects legitimate advice sought and is essential for the administration of justice and clients should take all steps to protect it.

In order to protect privilege, particularly in the corporate setting, clients should ensure there is early involvement of external counsel in sensitive or complex cases. Lawyers should be judicious to document the confidentiality of all communications – that means Memorandums and emails should be labeled “Privileged and Confidential,” but only in those cases where the communications are privileged and confidential. Communications from the lawyer should be restricted internally and externally to avoid accidental waiver. It should be noted that labeling communications that are not protected, such as those in furtherance of criminality, will not make them privileged.

Canadian and foreign clients (banks especially) should be careful about dealing with external lawyers in other countries where privilege is not as strong as in Canada when they contemplate sharing advice or files. That is because the external sharing in other jurisdictions with more relaxed privilege laws will weaken the privileged nature of documents. In Switzerland, for example, privilege of legal communications does not apply to in-house counsel at banks, NGOs and other institutions.

Only Lawyer’s Advice is Protected

Banks often believe that accounting or advisory firms that provide anti-money laundering advice or compliance reviews are protected by privilege but that is one example where there is no privilege attached to the advice because legal privilege can never attach to advice from non-lawyers, no matter how qualified such advisors may be to give compliance advice. The exception here again is where the non-lawyer, such as an investigator, is part of a litigation team where litigation has been commenced or in clear contemplation, and in that instance, privilege attaches to all the communications as litigation and normal privilege.