Since the FBI released parts of its file on the Russian Ten investigation in 2011, and CBS “The FBI Declassified” covered the story in depth this October, the public has gained a better window of visibility on one of the longest, deepest covert operations ever carried out by a foreign government in the US, and one of the longest FBI investigations – an investigation which shed light on the way deep covert activities are taking place that involve Canada.

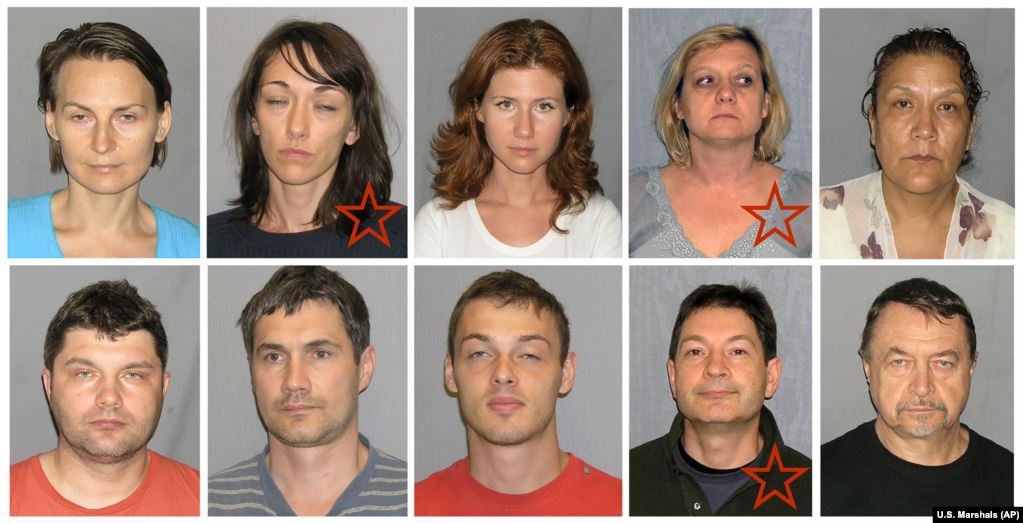

The 3 with stars obtained real Canadian identity products from Canadian government agencies in the names of deceased persons to immigrate to the US and commence spy operations as foreign agents.

The Russian Ten were ten secret agents and four other operatives from Russia who worked for the foreign intelligence organ of the Russian Federation, the SVR, in various cities in the US for several years. Their secret mission? To assume fake identities and live in the US long term, immersing themselves into US society and culture and to use that penetration to develop close ties with US policymakers and report intel back to the SVR that would give Russia a competitive advantage.

After a multi-year surveillance and investigation program undertaken by the FBI, they were arrested in the US in June 2010, after they had spent several years there at various universities and in US businesses.

Many of them came to Canada first because that is a common way for Russians to infiltrate the US, possibly because either immigration visa standards are more relaxed to enter Canada than the US, or because false identity products are easier to acquire from Canadian government agencies and pass off in Canada, or perhaps a bit of both.

Four of the Russian Ten were fake Canadians – Donald Howard Heathfield, Tracey Lee Ann Foley (who was married to Heathfield), Christopher Metsos and Patricia Mills.

The FBI files reveal how at least one of them acquired a fake Canadian identity after landing in Canada from Russia from a death notice in the newspapers.

According to the FBI files, Andrey Bezrukov assumed the identity of Donald Heathfield (who was deceased) and obtained a real Canadian birth certificate from the Quebec government using information from the death notice of the father, Howard William Heathfield, who died on or around June 25, 2005.

His spy wife, Tracey Lee Ann Foley, did the same – assuming the name of a dead Canadian child in Quebec. Her real name was Elena Vavilova. They lived in Toronto and had two children, even starting their own diaper business as part of their cover. Their cover was so good, the Toronto Star ran a story about their entrepreneurial spirit launching a Toronto diaper business. Often intelligence agents are paired up at headquarters long before they head out to a transit country like Canada before being deployed to the US.

Many of the Russian Ten pursued advanced degrees in the target country and joined professional organizations to deepen their cover and hide their activities as Russian intelligence agents.

Ultimately, they sought contacts with American businessmen. Two of the Russian Ten, for example, Cindy and Bradley Murphy, sought to develop contacts in the financial services sector and among venture capitalists.

Heathfield attended Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government and remained active in its alumni association to gain access to government and academic influencers and authority figures. He launched another start-up subsequent to the diaper business, providing business forecasting services which were marketed to the military and government. It didn’t actually have operational tech or sales – the business was a merely a cover for clandestine activities, materially as a way to gain entry to critical connections who might have intel of value to Russia.

Another Russian operative who was able to obtain a Canadian passport using a stolen identity, Christopher Metsos, was a handler who provided operational support such as money and tradecraft for the Russian agents operating in the US. In order to fund operations without traceability, Metsos delivered bags of cash to agents in the US to fund their lifestyle and activities.

Two others, Anna Chapman (aka Anna Vasilyevna Kushchenko) and Mikael Semenko entered the US later using their real names and with different tradecraft which the FBI assessed posed greater risks to US national security at that time. Chapman was named “Agent 90-60-90” by the SVG, a sexist reference to her bust, waist and hip size. Chapman and one other spy acted as realtors, and used the real estate sector and business connections in that sector for influence.

After their arrests, the existing US administration negotiated a spy swap with Russia so that the resolution of the cases was handled through intelligence channels which minimized collateral damage.