Cruel and unusual punishment

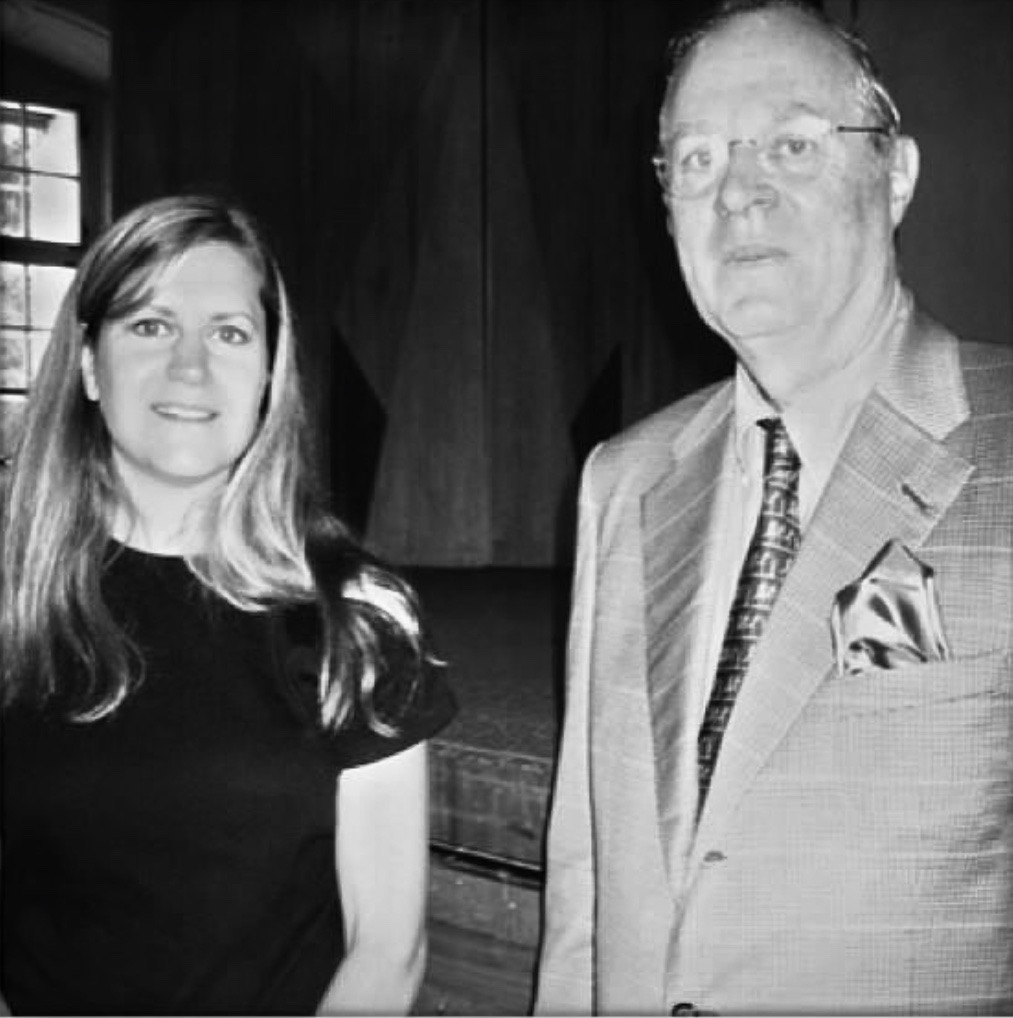

Everything I know about the Eighth Amendment and death penalty jurisprudence, I learned from former US Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy, from whom I had the privilege of studying law during a course on international human rights and constitutional law.

US Supreme Court Justice Kennedy, as he was then, was not my law professor but he educated our American law school class on death penalty jurisprudence. I mention Justice Kennedy because what emerged from his class was the foreseeability that the day would come when a foreign country may cease to provide intelligence or evidence to US government agencies because of the Eighth Amendment of the US Constitution and the death penalty.

It seems that day has arrived.

UK pausing handing over MLAT evidence because of Court ruling

A few days ago, British authorities, according to media reports, informed the US Department of Justice that it has suspended providing evidence to the US government in connection with investigations because of the death penalty in the US (and by implication, its interpretation of the Eighth Amendment).

Relying upon the decision in the UK Supreme Court in Elgizouli v. Secretary of State for the Home Department [2020] UKSC 10, on appeal from [2019] EWHC 60 (“Elgizouli“), the UK government has apparently declined to provide assistance under a mutual legal assistance treaty (“MLAT“) to the US in connection with a Visa fraud case. All things considered, Visa fraud is not considered in all countries to be a major criminal offence.

The UK is said to have informed its US counterparts that it has paused the provision of evidence to all countries with the death penalty on the books, not just the US, because of the Elgizouli decision. But the Elgizouli decision is about more than the death penalty.

So, what happened in the Elgizouli case that altered the legal landscape and paused international MLAT cooperation for law enforcement investigations, even low grade ones, among the US and the UK?

ISIS terrorist activities against humanity

Elgizouli is a case that has to do with the prosecution of members of a terrorist organization who engaged in terrorist activities.

During the time in which the Sunni terrorist organization called the Islamic State (“ISIS“) controlled territory in Iraq and Syria and set up a pseudo state, it commenced a campaign of kidnapping foreign nationals, beheading them, filming the beheadings and publishing the filming of the murders on Twitter and other social media channels.

Among those captured and beheaded were James Foley, Steven Sotloff, Peter Kassig, David Haines and Alan Henning. In one case, a Jordanian member of the military was set on fire in a cage and his death was filmed and posted on Twitter. Thousands of Yazidi children and teenage girls were kidnapped, trafficked, sold and forced into sexual slavery by ISIS.

With the collapse of ISIS, their members fled to refugee camps, fled to Turkey, fled to houses to pretend to be non-ISIS and others were captured by Iraq, Syrian or Kurdish law enforcement agencies.

27 beheadings of US citizens and others

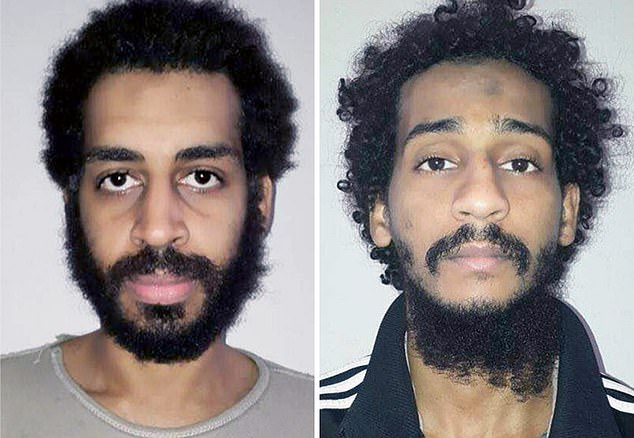

Two ISIS men implicated in the ISIS social media beheadings and killings of 27 foreigners, el Shafee el Sheikh and Alexanda Kotey, were captured by the Kurds in January 2018. el Sheikh lived in ar Raqqah during the time of ISIS.

It turns out that both are British foreign nationals. Because they originated from the UK and are implicated in the murder of US citizens in Syria, and are members of a terrorist organization which was responsible for the commission of heinous crimes against humanity, US law enforcement seeks their presence on US soil to prosecute them to provide justice for the families and for the global population harmed by ISIS.

The UK Supreme Court called the acts in which they are implicated as “the worst of the worst” and noted that their prosecution is an aim “shared by all right-thinking members of our society.”

MLAT request from US for criminal investigation

The US Department of Justice, pursuant to a 1994 MLAT with the UK for criminal matters, made a request of the UK government for files, data, personal records and such in connection with both of the ISIS men. The UK government made a decision to provide to the US government, the personal and other information in respect of the two ISIS men and in its correspondence to the US government sought assurances that the death penalty would not be sought.

When making the decision to hand over personal information and evidence, the UK government did not consider the relevant UK privacy legislation, the Data Protection Act 2018 (the “Data Act“). In all, the UK government collected, processed and formulated over 600 separate documents of el Sheikh. It is clear that the UK government provided the information verbally to the US government in respect of el Sheikh but not clear whether it handed over any physical files comprising the 600 documents.

Sometime after July 2019, el Sheikh and Kotey were handed over to the US government in Syria by the Kurds. Their whereabouts are unknown. el Sheikh has since been stripped of UK citizenship in connection with his terrorist activities.

MLATs are treaties among countries for the provision of evidence and personal information restricted to criminal matters, even if the criminal matter is at the investigation stage, as was the case here. However, there is anecdotal evidence that MLATs are used (abused) for investigations and to collect foreign evidence for matters that are not criminal, such as for civil or regulatory matters under non-criminal statutes.

Concerns over cruel and unusual punishment

In response to the UK government, US authorities informed it that the death penalty under its federal law was an option and that if it sought the death penalty as against el Sheikh, it would not use evidence obtained from the UK under the MLAT for that purpose.

In the meantime, prosecutors in the UK determined that they did not have sufficient evidence to prosecute el Sheikh in the UK, meaning that if he returned to the UK, he would be free. The UK government then formed the belief, after consulting with US prosecutors, that the prosecution of el Sheikh would only be viable if the US relied upon the evidence obtained pursuant to the MLAT by UK authorities. In other words, it became a “but for” proposition according to the UK.

Judicial review of UK government decision to provide evidence to the US

A few years later, the mother of el Sheikh, Ms. Elgizouli, became aware from a newspaper article that personal information and evidence of her child had been provided (at least verbally) to the US government and that a decision had been made to physically provide it to the US government pursuant to an MLAT. She filed a judicial review for a review of the decision of the UK government employee(s) and official(s) who made the decision to hand over evidence to a foreign country.

Her solicitor sought a judicial review on two grounds: (a) at common law, it was unlawful for the UK government to provide information under an MLAT or otherwise, to a foreign state that may be used in furtherance of a prosecution in that state where, upon conviction, sentencing may involve the death penalty; and (b) irrespective of (a) above, the provision of personal information of a person by the UK government was unlawful under the Data Act (similar to Canada’s PIPEDA).

UK Supreme Court decisions

In January 2019, Elgizouli’s judicial review application was dismissed by a UK Court, which held that the provision of information to the US government was lawful on both grounds – as a matter of the MLAT and under the Data Act.

Elgizouli then successfully appealed the lower court decision to the UK Supreme Court.

Ground one – constitutional violation

Lord Kerr, writing for the majority, held that the decision of the UK government to provide evidence to the US government in such circumstances was unlawful on both grounds – the MLAT and as a matter of privacy legislation.

On ground one – the MLAT – relying upon the Bill of Rights, 1688 (which is the law in Canada as well), the constitutional instrument, the Court held that cruel and unusual punishment is prohibited, and that the death penalty ( and its average 12 year incarceration waiting time), constitutes cruel and unusual punishment. The material parts of the UK decision hold that a state agency cannot use its powers in furtherance of punishment that may be inhumane (an Eighth Amendment consideration). The cruel and unusual punishment is determined in reference to UK law (e.g., the law of the MLAT provider not the MLAT requester).

The Court held that it was fundamentally illogical to refuse to extradite persons to death penalty countries yet to proceed to provide those same countries with evidence pursuant to an MLAT for prosecution where the outcome may be the same, without obtaining written undertakings as a condition precedent that the person will be treated to punishment consistent with the MLAT providing country (e.g., no death penalty).

The Court held that it was against the common law for the UK to facilitate a death penalty country in its prosecution of any person where that person’s life and liberty is in peril and they may be executed, irrespective of if the exercise of power to provide MLAT evidence is an exercise of the prerogative powers – a key point because a prerogative power is a residual power held by the Queen and her delegatees in places like Canada. Prerogative powers when exercised, are not subject to review in the same way, and hence the Court made the point of holding that the decision applied to the exercise of the prerogative power in MLAT matters.

Ground two – privacy law violation

On ground two – privacy legislation – the Court held that the decision to provide evidence of el Sheikh to the US government was unlawful as it was a violation of the Data Act. The UK government argued that in these circumstances, it was entitled to rely upon a provision of the Data Act that authorizes the disclosure of a person’s personal information, despite the violation of privacy, when a controller or competent authority provides the information for a law enforcement purpose upon request.

The UK Supreme Court said absolutely not.

It held that the collection and processing of evidence of el Sheikh was not lawful and that the law enforcement purpose for which it was sought was not legitimate. The purpose cannot be legitimate if it is inconsistent with UK law and it is inconsistent with UK law because of the risk in this case, however remote, of the defendant being subject to cruel and unusual punishment by virtue of the death penalty being on the table.

In addition, the fact that the UK government made a decision in respect of the sharing of personal data of a citizen to a foreign state for law enforcement purposes without appropriate safeguards in place to protect its citizen made it unlawful. The Court held that the only circumstance in which personal information or intel may be provided in such circumstances as arose here, is in an emergency situation in order to save lives or to protect the security of a nation.

What about MLATs sent to Canada?

UK law is applicable in Canada, especially the Bill of Rights, which is a constitutional instrument in Canada that is part of constitutional law, considered to be an always-speaking statute.

As a result of the Elgizouli decision, one can imagine that eventually a number of defence lawyers in Canada may challenge evidence provided to US regulatory agencies and law enforcement under MLATs on the dual grounds of an Eighth Amendment (Bill of Rights) argument and on the PIPEDA argument, even irrespective of the death penalty. That’s because what is considered cruel and unusual is in reference to the requestee, not the requestor, state, and the jurisprudence in that regard has dealt primarily with the the lengthy terms of incarceration while appeals progress and such, leading up to the termination of a convicted prisoner. The position against cruel and unusual punishment is a fundamental principal of justice in Canada (and per the Burns case, implicates the right to life, liberty and security).

Recollect that the UK is said to have refused an MLAT request of the US for an alleged Visa fraud case, where no death penalty is implicated.

MLAT may become a prosecution by proxy

One needs to recollect as well, vis à vis Canada as a country in which the death penalty has been abolished, that the law is that there is an obligation not to expose an accused to the real risks of its application, and not to provide the crucial link in the causal chain that would make such possible, a principle that is considered to have a wider application than in extradition. While merely persuasive, the special rapporteur for the United Nations on human rights took the position that the above obligations of death penalty abolitionist countries “extends to intelligence and incriminating evidence.” A prosecution by proxy is the concern and here the “but for” analysis arises, mentioned above. If Canada undertakes a “but for” action against one of its citizens (but for Canada providing evidence under an MLAT or otherwise that leads to the imposition of cruel and unusual punishment of one of its people in a foreign country, which would not have happened but for Canada’s help), it is prosecuting by proxy.

The Elgizouli case suggests that MLATs must be strictly complied with as to their terms and that undertakings as to punishment consistent with the law of the requestee, may have to be given by the requestor as a condition precedent of evidence being provided, and must be given in cases where the criminal investigation could lead to charges where the death penalty is available upon a conviction. Pursuant to Elgizouli, any disclosure of person information must be consistent with federal privacy legislation and have attendant safeguards attached to the disclosure thereof. Otherwise, the provision of evidence may be challenged years later when a person learns that they were secretly the subject of an MLAT. The cause of action to challenge a secret MLAT under judicial review, based on this case, arises when the MLAT becomes known to the person.

ISIS Beatle

The ISIS Beatle is not exactly a likeable character irrespective of the crimes he is alleged to have committed. Its notable that the UK Court, as it should, considered the law and not the character of the parties in the judicial review. The flippant and condescending personality of el Shafee el Sheikh is evident in this interview, below. Among other things, he refuses to look at the woman reporter (because she’s a woman), calls the FBI the least respectable among investigators with whom he encountered since his captivity by the Kurds, and refuses to denounce slavery.

Sources:

(1) Carol Steiker and Jordan Steiker, Justice Kennedy: He swung left on the death penalty but declined to swing for the fences, SCOTUSblog, July 2, 2018.

(2) Elgizouli v. Secretary of State for the Home Department [2020] UKSC 10, The Supreme Court, March 25, 2020.

(3) Britain briefly suspends sending evidence to US law enforcement, in move some see as a sign of fraying relationship, Washington Post, June 10, 2020.

(4) MEMRI TV YouTube Channel, British ISIS ‘Beatle’ El Shafee El Sheikh in Interview from Captivity: I Don’t Denounce Slavery, April 11, 2018.