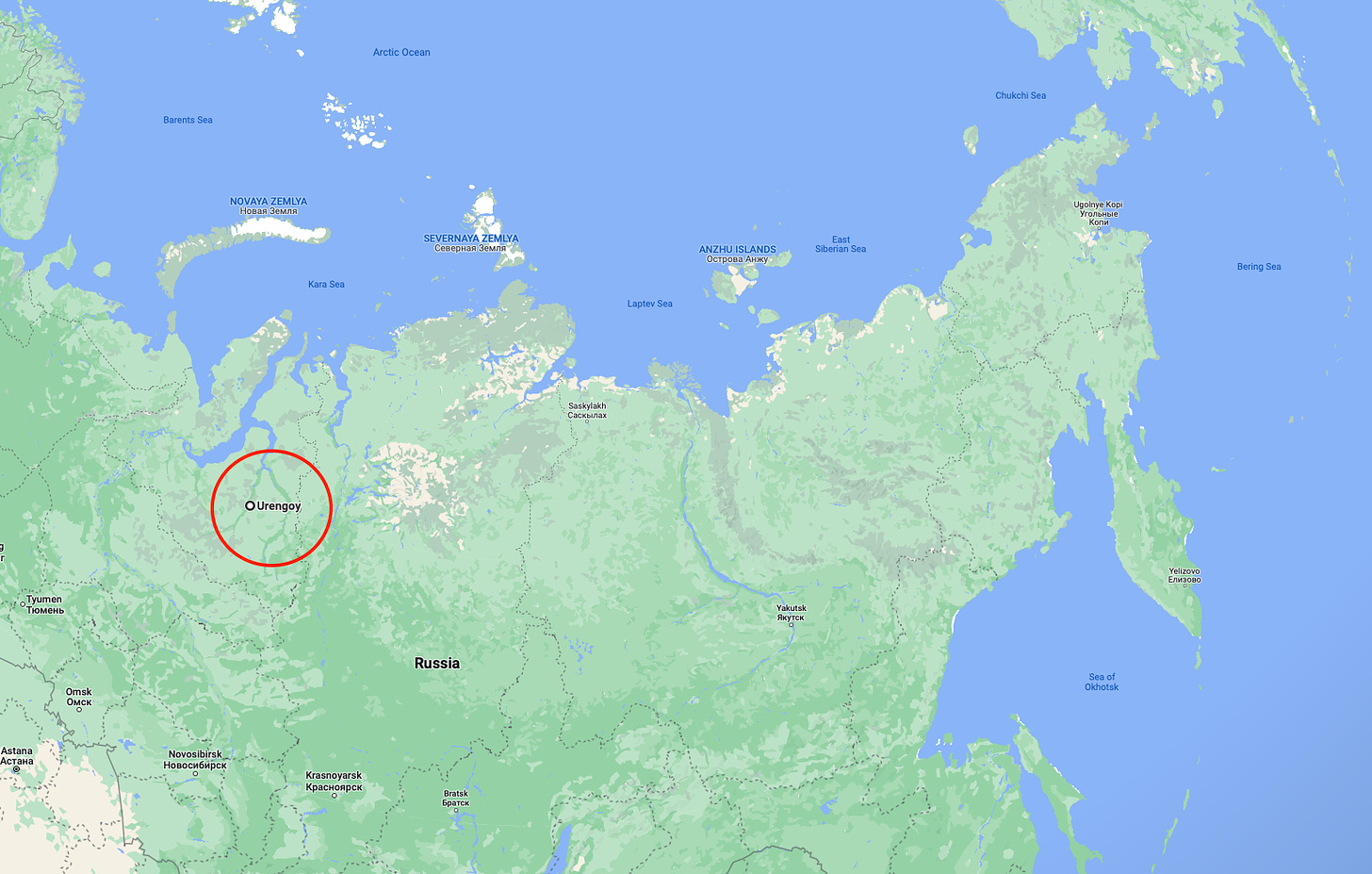

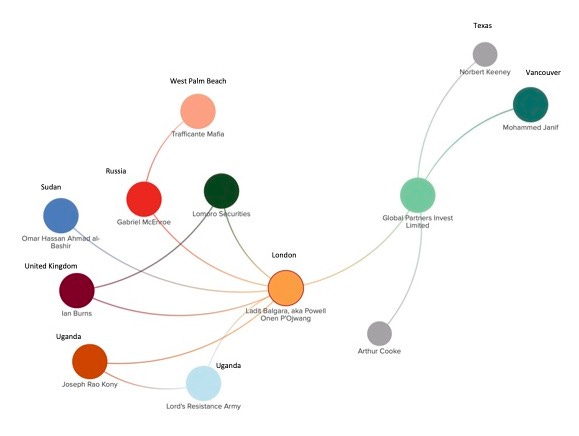

Vancouver’s most infamous heroin supplier, Naji Sharifi Zindashti, and his trial in Turkey involving Vancouver

Corruption, heroin, and murders

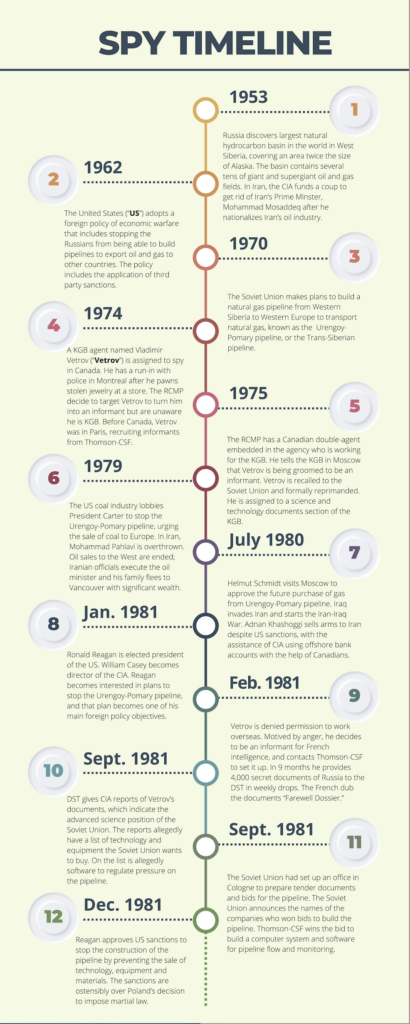

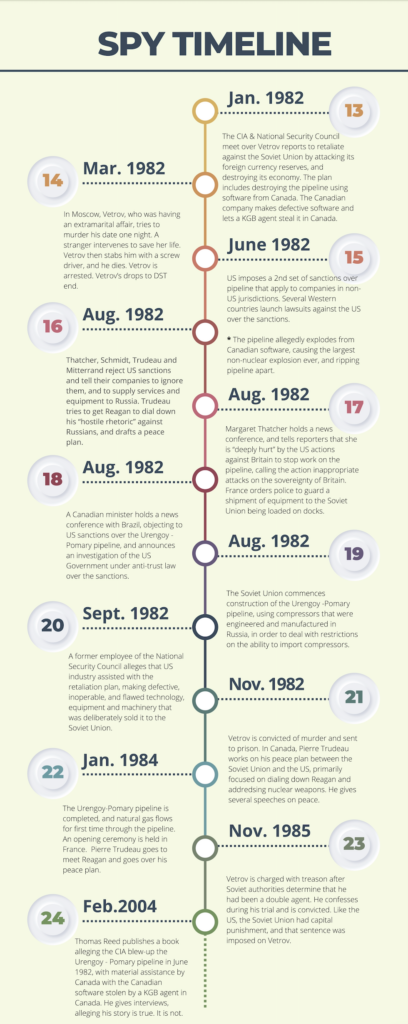

If you’re from Vancouver, you know the story of how, in 2016, two Vancouver local gang members, Harpreet Singh Majhu and Orosman Jr. Garcia-Arevalo, agreed to travel to Dubai and murder an international drug lord named “Cetin Koc” for money.

After the hit, they fled back to Vancouver, and a month later, they were found dead in Vancouver. They were allegedly killed by individuals who are in business with the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corp. in Vancouver. Or so Iran-watchers believe.

The drug lord murdered in Dubai, Cetin Koc, was an Iranian who obtained Turkish citizenship under a fake name.

Another Iranian drug lord – a more powerful one in the heroin trade – Naji Sharifi Zindashti (Farsi ناجی شریفی زندشتی) is accused of hiring the two Canadians to murder Koc, as well as organizing other murders and kidnappings around the world, some on behalf of the Iranian intelligence services, MOIS, and the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corp.

Naji Sharifi Zindashti was arrested in Turkey, charged, and mysteriously released from jail. Pay-offs and bribes to lawyers, prosecutors and judges, were alleged to have been behind his release. He now remains within the safer confines of Iran, Iraq and Azerbaijan.

A wide-ranging murder trial involving multiple defendants, including Naji Sharifi Zindashti, and involving the murders and kidnappings, is slowly taking place in Istanbul after six years.

But the trial has experienced a few new twists – one of the defendants brought a witness to the trial in Istanbul who is the real Cetin Koc – the drug lord killed by the two Vancouver killers in Dubai.

The Court refused to hear from the alive Cetin Koc and referred the matter to the prosecutor to investigate. Because Naji Sharifi Zindashti is charged with hiring the two Canadians to murder Cetin Koc, if Cetin Koc is alive, that murder charge goes away. The revived Cetin Koc is not the drug lord; he is a shepherd. Cetin Koc used the identity of the shepherd in Turkey. The real name of the murdered drug lord was Parvis Kashavarz Omarabadi.

So who did the two Canadians kill in Dubai if not Cetin Koc? Omarabadi? Someone else?

Another twist in the story is a massive corruption scandal involving the Turkish judiciary, which has throw a wrench in proceedings involving Zindashti and his alleged ordered hits in Canada and elsewhere.

A month ago, two reports were allegedly sent to the government about corruption of judges and prosecutors, including one from Turkey’s intelligence services, MIT. The Turkish government alleges the report sent to MIT does not exist. According to both reports, prosecutors and judges are accepting significant bribes to release or detain defendants, lose evidence, or render decisions favourable to whomever pays them. Journalists who were given copies of the reports noted a stark omission – the cases of Naji Sharifi Zindashti, and Orhan Ungan, and the judicial pay-offs and murders of witnesses connected to their trials.

The reports were commissioned in part because the person accused of murdering Zindashti’s daughter, Orhan Ungan, alleged that there is an organized gang within the judicial system, and that gang of judges and prosecutors accepted millions of dollars from Zindashti to keep Orhan Ungan behind bars for four years.

The judicial corruption scandal threatens to undo the cases against Zindashti.

The cases against Zindashti are relevant to Canada because they offer the only visibility on how an international heroin trafficker hired the two Canadians, and the connection, if any, of the IRGC to their murders in Canada. According to Turkish authorities, the long arm of MOI and the IRGC extend into many countries for operations that are carried out with the help of Zindashti’s transnational criminal organization. In essence, what Turkey says is that where the Zindashti transnational criminal organization traffics to, and works in, is where they help MOI and the IRGC, and vice versa.

One of the places where the Zindashti transnational criminal organization traffics to, and works in, is Vancouver. Zindashti’s cousin, Hussein Karimi Rikabadi, the so-called king of heroin in Romania, shares the Vancouver territory.

To understand what is going on, and how heroin trafficking and the IRGC play a role in our Vancouver murders, we start at the beginning, with a look at who is who.

The characters

Cetin Koc: An Iranian shepherd whose name was used by an Iranian heroin trafficker, Parvis Kashavarz Omarabadi, in Turkey. Omarabadi was murdered in Dubai.

Harpreet Singh Majhu and Orosman Jr. Garcia-Arevalo: Two Canadians who traveled to Dubai and murdered Omarabadi. They were then murdered in Vancouver.

Arzu Sharifi Zindashti: The daughter of Naji Sharifi Zindashti. She was murdered.

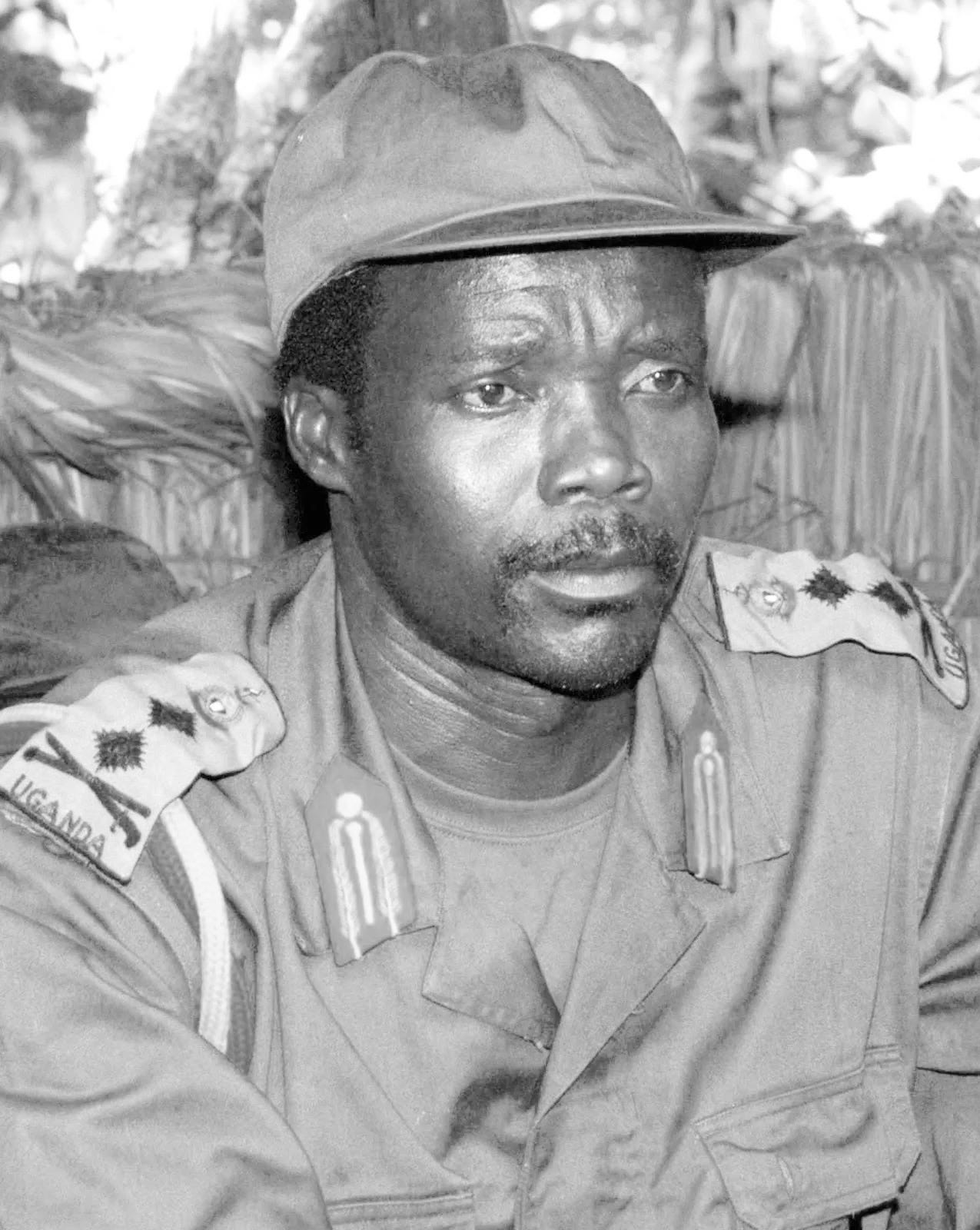

Naji Sharifi Zindashti: A well-known international Iranian drug lord, who specializes in bulk heroin trafficking, tied to the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corp.

Orhan Ungan: An Istanbul-based drug trafficker, who is part of the Istanbul Mafia, and a rival of Zindashti.

Ilhan Ungan: The brother of Orhan Ungan. He was murdered in Istanbul.

Kudbeddin Kaya: The lawyer of Orhan Ungan. He was murdered in Istanbul.

Habib Chaab: An Iranian dissident who was kidnapped in Istanbul and transported to Tehran. His real name was Saberin Saadi. He is dead.

Burhan Kuzu: A lawyer, prominent government official, member of President Erdogan’s AKP party, and advisor to President Erdogan of Turkey. He is dead.

Zekeriya Oz: A prosecutor who released Naji Sharifi Zindashti from jail in 2010.

Cevdet Ozcan: A judge who released Naji Sharifi Zindashti from jail in 2018.

Murat Garki, Haci Osman Sezen, Turgay Akar, Ali Ekber Akgun, and Sjaak Burger: Drug traffickers murdered in Amsterdam, Istanbul and Panama.

Aliye Uzun: A member of President Erdogan’s AKP party, who allegedly provided a prostitution service. She was shot in Istanbul.

Sedat Peker: A famous member of Turkish organized crime, who is now a YouTube independent reporter on organized crime and corruption in Turkey. If you are following our series on Voyager Digital, the Vancouver crypto outfit, the upcoming Part 4 on Russian organized crime in Canada’s mining sector also features Sedat Peker.

The drug arrest

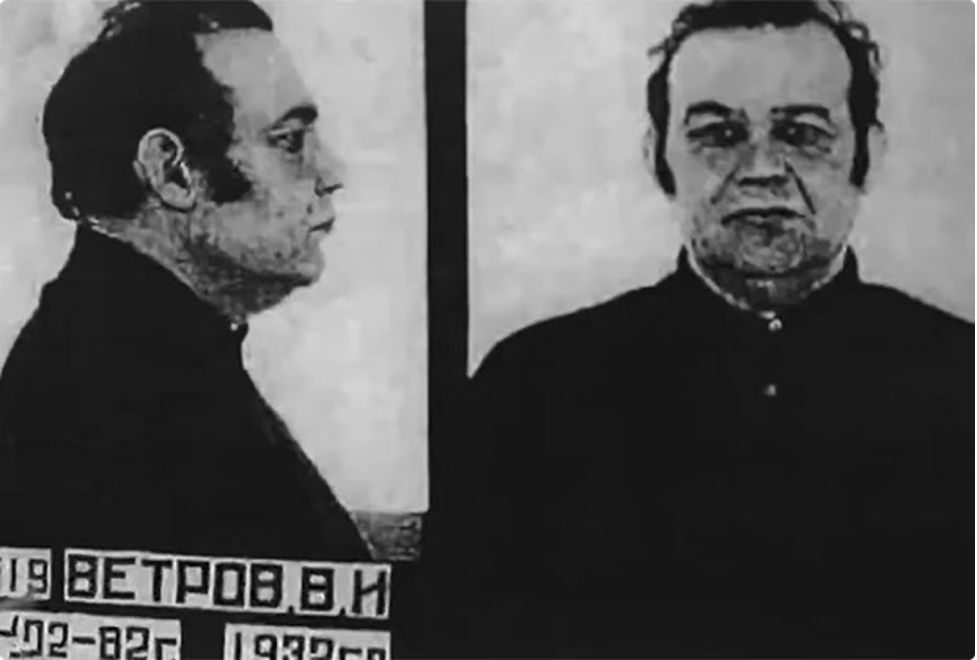

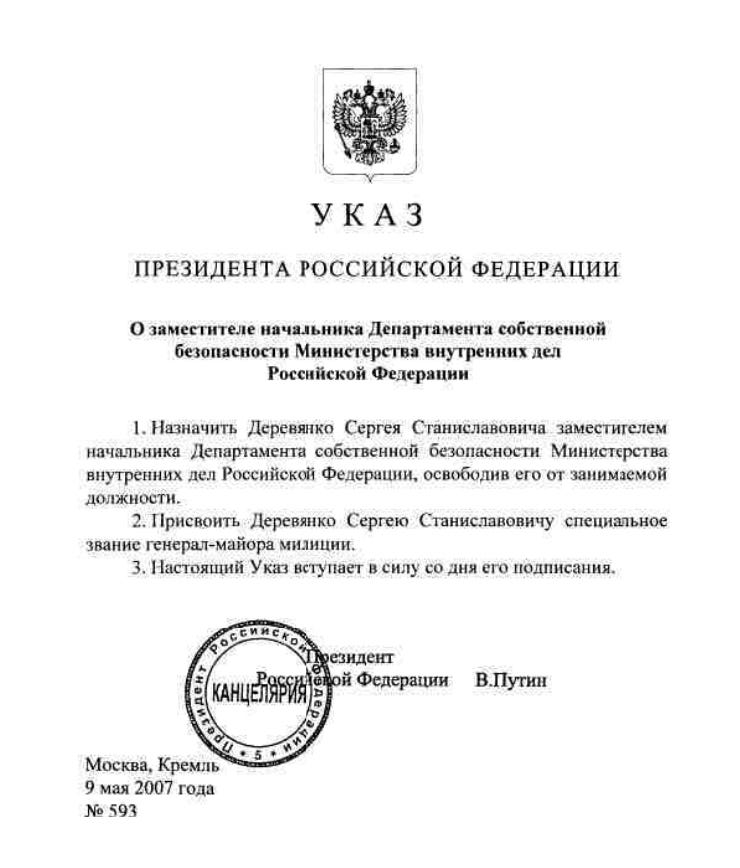

Zindashti first came to the attention of law enforcement in Turkey in 2007, when he was arrested in Istanbul with 75,300 kilograms of heroin. He was living in a mansion in Istanbul at the time, with his daughter, Arzu Sharifi Zindashti.

He was detained pending a trial. In 2010, he was released and the drug trafficking case was halted by the chief prosecutor, Zekeriya Oz, after Zindashti agreed to become a witness in conspiracy trials being held against defendants accused of an attempted coup against the government. Zindashti alleged at the time that a criminal defense lawyer named Kudbeddin Kaya was paying-off prosecutors and members of the judiciary to dismiss drug cases. Some say Zindashti paid significant bribes to Oz for his release in 2010.

Today, Oz himself is on the run, for having allegedly joined a more recent coup attempt. He is believed to be in Germany.

The Greek heroin bust

When he was released, Zindashti returned to his mansion in Istanbul, and continued his heroin trafficking business. He also became an investor, and used the proceeds of heroin trafficking to invest in numerous businesses in Turkey.

In 2011, he became acquainted with Aliye Uzun, a member of the AKP party. She denied knowing or even meeting Zindashti but when pictures emerged of them together, she later said that she was hired by him as an immigration lawyer, to help him obtain Turkish citizenship, which she was unable to do because of his criminal record; she also then said that she was his girlfriend when other evidence emerged. Zindashti alleged that, at this time, she ran a prostitution service, procuring women for him and for Turkish members of the judiciary and of government.

That year, Zindashti met and became friends with Burhan Kuzu, President Erdogan’s constitutional law advisor and a leading member of government.

By 2014, Zindashti’s daughter was attending the University of Istanbul; Zindashti’s nephew from Iran was living with them in the mansion, and he attended university with her.

That summer, a Greek informant walked into a police station in Athens and reported that two tons of heroin were stashed in warehouses and airport hangers, and was about to be removed and trafficked across Europe. The Greek police went into action; 33 people were arrested; the drugs were seized.

Behind the heroin operation was Cetin Koc in Dubai, aka Omarabadi, whom we are going to refer to by his stolen name to keep things simple.

Cetin Koc came to believe that Zindashti was aware of the heroin operation in Greece, and that Zindashti had gone to prosecutor Zekeriya Oz with the information, and that Oz had alerted Greek authorities.

Murder of Zindashti’s daughter

Cetin Koc wanted revenge against Zindashti for the loss of his shipment of drugs. He asked the two Ungan brothers – Orhan Ungan and Ilhan Ungan – to kill Zindashti in Istanbul. The Ünğans were his partners, and members of the Istanbul mafia.

In September 2014, Zindashti’s daughter, Arzu Sharifi Zindashti, and his nephew were gunned down in her car on their way to university. The hit was a miss – Zindashti was supposed to be in the car.

Zindashti gave a short interview to the media in Istanbul and said that he had received death threats but did not think his children would be targeted. Before the murder of his daughter, his friend Esfendiyar Rigi disappeared in June of that year.

After the death of Arzu Zindashti, an organized crime war of revenge started that would see at least 20 people tied to organized crime or their lawyers, killed; mostly they were tied to Cetin Koc’s operation, and people believe Zindashti was behind them.

War of revenge

On December 11, 2014, Murat Garki, a cocaine drug lord, was killed in Amsterdam.

Then, Haci Osman Sezen and Turgay Akar, who killed Garki, were killed in Istanbul.

Two days later, Aliekber Akgun, another drug dealer, was killed.

The same day, Vedat Sahin and Ferdi Topal were killed in Istanbul.

And on December 31, 2014, Okan Fidan was killed in Amsterdam.

In January, in Panama, a drug dealer named Sjaak Burger, was killed. In Istanbul, Beyhan Demirci was killed.

In August 2015, Orhan Ungan was arrested in Amsterdam for organizing the murder of Arzu Zindashti, and extradited to Turkey. His brother, Ilhan Ungan was arrested in Istanbul. Orhan Ungan is not an unknown underground figure in Europe – he says that he ran a large vehicle theft and importation business, stealing cars from the West and reselling them in other countries, and he alleges that he worked for Dutch intelligence.

We know what happens next from the Canadian side – Zindashti put feelers out for a paid hit on Cetin Koc in Dubai and two Vancouver organized crime figures answered the call. The operation was planned for over a year, and there was no last minute engagement of the two Canadians. When the time was set, they traveled to Dubai, where they were given weapons, ammunition, a vehicle, and the address and pictures of Cetin Koc.

On May 4, 2016, the two Vancouverites killed Cetin Koc in his vehicle and fled Dubai.

The United Arab Emirates quickly identified the two Canadians as the ones who carried out the hit.

I was not following this story at the time but at a social event, I was told by a Canadian law enforcement person that they considered the two Vancouver hit men as having idiotically gone to Dubai to carry out the hit, not understanding with whom they were dealing or the risks to themselves. I do not know if the Canadian law enforcement person knew of Zindashti’s role at the time but I got the impression they knew that Koc was a significant international drug trafficker, and this was no ordinary hit.

The order was then given to eliminate the two Vancouverites – Garcia-Arevalo and Majhu. The hits were carried out in British Columbia by professionals. Garcia-Arevalo was shot to death on May 11, 2016, and his body was found in a blueberry field. Majhu was found dead on June 10, 2016, in Agassiz, in a burnt-out vehicle.

Why kill them in far away Canada?

To get to the answer, we must realize that Vancouver is a well-known epi-centre of the confluence of three groups who work together – (1) the Hells Angels; (2) the Big Circle Boys from Guangzhou; and (3) wealthy regime families from Iran who are part of, or tied to, the IRGC, and work the heroin trade. The way the heroin trade works in Vancouver is that wealthy Iranians import heroin, the Hells Angels handle distribution, and the Big Circle Boys handle the money movements back to Turkey and Iran, using, among other methods, bulk cash shipments, crypto OTC brokers who operate in luxury hotel penthouses in Vancouver and Toronto, and Iranian money services businesses (one Chinese-owned crypto exchange in particular near the Iranian money services businesses, all situated in North York, Ontario). The two Vancouver murderers had to have been paid somehow, by someone, before they got on the plane to Dubai.

Something about how they were paid and contacted in Vancouver, led back to Zindashti, his cousin Hussein Karimi Rikabadi, Iran, or the IRGC, and that’s why they were killed – it had to do with knowledge. Recollect that the operation was a year in the making – that was a lot of time for the two Vancouver gangsters to pick up information, and vice versa.

In Istanbul, other killings occurred, including the murder of Kudbeddin Kaya, the lawyer of Orhan Ungan, in November 2017. Kaya had been arrested twice before for bribing the judiciary, and being a terrorist.

In Tehran, Koc’s brother was kidnapped. Allegedly, his body was then found in southeastern Turkey.

And in April 2019, Ilhan Ungan was killed in Istanbul. His brother blamed the politician and lawyer Burhan Kuzu for his brother’s death, and launched a lawsuit against him, claiming that Burhan Kuzu accepted pay-offs from Zindashti to manipulate the system against the Ungan brothers.

Arrest of Zindashti

After Orhan Ungan was arrested for murdering Zindashti’s daughter, he alleged that the series of murders in Canada, Dubai, Panama, Netherlands, and Turkey were revenge or clean-up killings by Zindashti tied to the murder of Zindashti’s daughter. Turkish police say that they located evidence that it was Zindashti who hired and paid the two Canadians to kill Cetin Koc in Dubai.

Orhan Ungan also alleged that Zindashti was an informant for the US government. We know this cannot possibly be true because he would have been executed in Iran for that.

In April 2018, the Turkish police decided to arrest Zindashti in connection with all of the revenge killings. By now, he was living in a villa outside Istanbul, where he was arrested with nine other men on his team, some of whom were members of law enforcement.

In October 2018, Zindashti was released by a judge named Cevdet Ozcan, who said at the time that there was no evidence tying Zindashti to the murders. That was untrue. Behind the scenes, another lawyer, and advisor of President Erdogan, was helping Zindashti. It was Burhan Kuzu, and it emerged that the only reason he even met Zindashti in the first place was because they were introduced by the lady figure – Aliye Uzun.

And you know what comes next – there are allegedly sex tapes and pictures.

Zindashti released

When Zindashti was released, he returned to Iran.

In Turkey, 20 men along with Zindashti, were eventually indicted related to 10 revenge murders, including those committed by the Canadians. The indictment alleges that law enforcement, as well as the judiciary, fed investigation information to Zindashti about his daughter’s murder to help him plan the revenge killings. It also revealed that Cetin Koc, the person killed by the Canadians in Dubai, had paid $5 million to the Ungan brothers to kill Zindashti.

The Ungan brothers were also indicted for the murders of Zindashti’s daughter but Ilhan Ungan was then murdered during the trial, and in October 2019, Orhan Ungan was acquitted. The acquittal was overturned on appeal.

In Turkey, people began to question why Zindashti was released, and also, how the Ungan brothers got released – all were charged with murders and being members of organized crime.

Judge Cevdet Ozcan was investigated for ordering Zindashti’s release and accepting a bribe of $3.5 million, which was delivered to him in cash by a jewellery store in the Grand Bazaar in Istanbul (this in itself is interesting – heroin traffickers are making payments in cash using jewellery stores – it is coincidentally the same method used in Macau to move proceeds of crime at mega casino complexes). In that investigation, he said that a senior AKP politician pressured him to release Zindashti because it was necessary for relations with Iran. The “senior AKP politician” was Burhan Kuzu.

Note what Ozcan was saying – he was saying that he was told that it was important to the Government of Iran, and therefore Turkey, for Zindashti to be released to continue doing whatever it was he was doing for Iran. Note also the clear importance of Zindashti to Iran. This means the Government of Iran communicated with Turkey and asked for Zindashti to be released; Turkey’s government officials then contacted the presiding judge.

What was the valuable thing that Zindashti was doing, or did, for Iran? We’ll get to that.

Blackmail and criminal pay-offs

In the meantime, it was leaked to journalists, including the organized crime figure turned YouTube journalist Sedat Peker, that Zindashti was pals with President Erdogan’s advisor, Burhan Kuzu.

Kuzu denied knowing Zindashti or having any connection to him. He wrote this to a journalist: “I neither know that Iranian nor have I ever met that judge (Ozcan)…I am a constitutional law professor. I know very well what putting pressure on the judiciary means.”

Journalists then published photographs of Zindashti and Kuzu, and other photographs of them with the lady figure, Aliye Uzun.

When the photographs came out, Kuzu then admitted he knew Zindashti, and he said the same thing as Aliye Uzun, that like her, he was hired to be his immigration lawyer to get him Turkish citizenship.

Burhan Kuzu then contacted Sedat Peker and gave him an interview. He also shared information and texts with Sedat Peker; one was about dealings with Iranian regime people.

For example, there was an exchange about moving a shipping container full of US cash to the West for a wealthy Iranian woman tied to the regime. That Burhan Kuzu even knew how to navigate the shipment of bulk cash stolen from Iran and get it to a Western country is astounding, let alone that it was something he seemed to do for underground people. It also speaks to the fact that Iranian regime people go through organized crime to move money because they have the established routes.

Peker is the one who put forward the allegation that Aliye Uzun had a side-gig of prostitution, where she obtained young girls for sex for Istanbul’s establishment. Zindashti alleged also that she was paid by him for prostitution services to procure young women. Specifically, he alleged that he paid her €500 per prostitute and she supplied six or seven women for an event Zindashti hosted.

According to Peker, in the beginning, Burhan Kuzu was being blackmailed by Zindashti and he had to keep doing illegal things for him. Later, when Zindashti was released, and after Kuzu was sued by Orhan Ungan, he then went to work for Ungan in order to make the lawsuit launched against him by Ungan go away, and he was also blackmailed by Ungan. What they both had over Kuzu was sex pictures or tapes – it is not clear – and allegedly evidence of bribery and pay-offs he had accepted to wave his magic wand and help make serious criminal cases against them disappear.

A lawyer named Ilker Dagli, who was the protégé of Burhan Kuzu, became wrapped up in the warped world of Burhan Kuzu and Orhan Ungan. He was Zindashti’s lawyer at one time, and allegedly, Kuzu filed a report alleging, apparently untruthfully that Dagli planned the murder of the Ungan brother, Ilhan. That was done so that Zindashti presumably would have to change lawyers. Someone recorded a video of a conversation of Dagli being blackmailed:

Blackmailer: “Kuzu has more things, brother, they have things … you understand?”

Dagli: “To be honest, whether it is Kuzu or not, it doesn’t matter to me. I threw it all away. Now I am asking myself – me – who they tried to kill, who escaped from them, will I have to pay the price for them?”

In 2020, Kuzu contracted Covid, was hospitalized and placed on a ventilator. He died of Covid, although some allege his ventilator was unplugged to kill him. Whatever secrets he knew about drugs, politicians, corruption, pay-offs, murder and sex tapes, died with him.

The Iranian dissident kidnapping

Then, in October 2020, an Iranian dissident named Habib Chaab, whose real name was Saberin Saadi, was convinced to travel to Istanbul to meet his ex-wife. He was an Iranian separatist who was living in exile in Sweden, from where he led a group called Harakat al-Nidal, which advocates for an armed coup in Iran to create a separate country carved out of Iran from the province of Khuzestan. Harakat al-Nidal is a terrorist organization under Iran’s laws.

When he got to Istanbul, Chaab was abducted by Iranians, anesthetized, shoved in a van, and driven to the Iranian border. In Iran, he was handed over to the IRGC and MOIS. Iran says that, in addition to planning an armed insurrection, Chaab was working with Mossad and Sweden’s intelligence agency, and was an informant for them.

In Iran, Chaab confessed to being involved in a coup attempt, and received the death penalty, which was carried out in Tehran.

The year before, another wanted Iranian who had fled Iran, Rasoul Danialzadeh, had been “returned” to Iran from Dubai in much the same way, with the help of Iranians in Dubai, presumably Iranian organized crime in the drug trade, working with the IRGC and Iranian intelligence.

And just before Chaab was kinapped, Gholamreza Mansouri, an Iranian judge who was wanted in Iran for corruption, was found dead in Romania under suspicious circumstances. Some people have tied his death to Zindashti because his cousin, Hossein Karimi Rikabdi, the well-known heroin trafficker, set up an organized criminal ring in Romania.

Circle back to Canada

Zindashti and twelve others associated with his organization in Istanbul, were accused of being involved in the kidnapping of Habib Chaab and working with the IRGC, using the Zindashti organized crime heroin trafficking ring in Istanbul to kidnap Chaab and transport him to the northern border.

The Turkish government, pursuant to an investigation it carried out, determined that Zindashti’s men, on behalf of the IRGC and MOIS, kidnapped Chaab from Istanbul. Charges related to the kidnapping of Chaab were added to the existing murder charges against Zindashti.

The gist of the new allegations are generally that, in order to carry out kidnappings or extrajudicial killings in other countries, the IRGC and MOIS use the services of local Iranian organized crime groups, and they work together to carry out hits and kidnapping around the world. And vice versa – sometimes the IRGC or MOIS will do the deed in a foreign country in support of the heroin trade.

That seems to explain what it is that Zindashti did, or does for Iran that prompted the Iranian government to seek his release in 2018. They need his transnational criminal organizations for operations.

But we also need to recollect the incident of the Iranian regime woman who knew to contact Iranian heroin traffickers to move a shipping container of cash to the West. This is not an insignificant story; it shows us the close ties among money movements, regime Iranians who move to the West, and the Iranian heroin trade run by transnational criminal organizations.

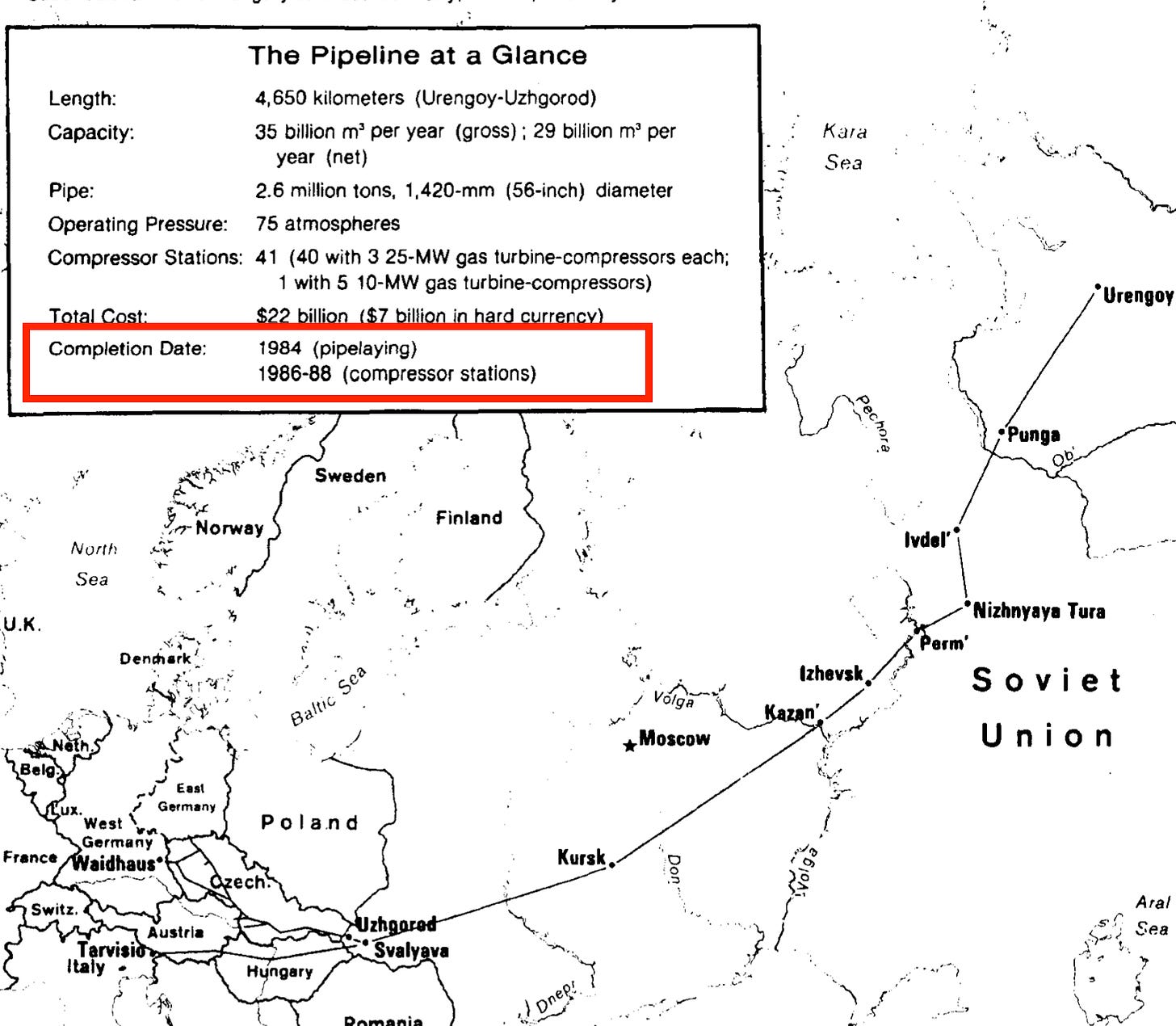

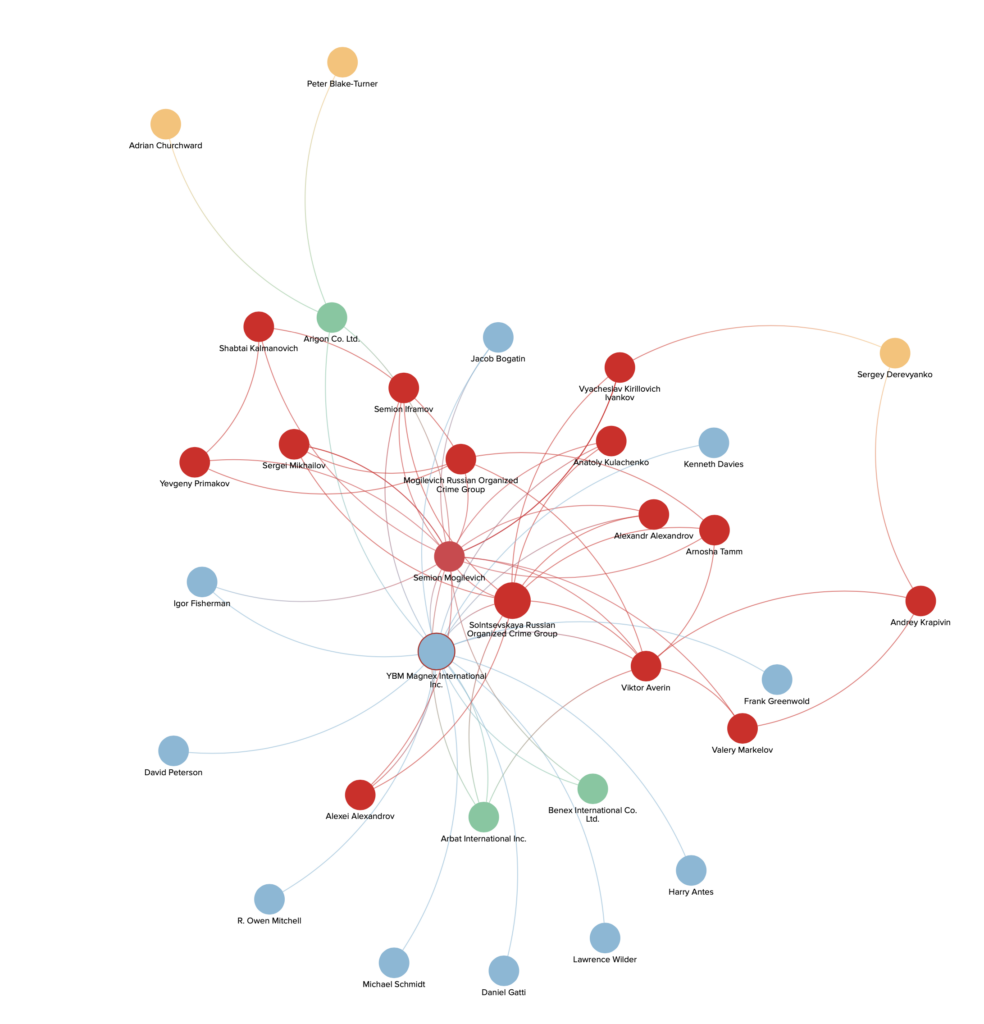

We know that Iranian transnational organized crime primarily is engaged in the heroin trade, and primarily from Turkey from where it is sent to Europe, and Vancouver, from where it is then distributed. The supreme leader of that worldwide activity is Zindashti.

If this is how things work, if the IRGC and Zindashti are in bed together and support each others operations, then we have our blue print as to what happened in Vancouver in 2016, when a body was found in a blueberry field and another in a burnt out car.

Don’t take my word for it — see here about how General Qasem Soleimani (killed extra-judicially by the US) is alleged to have paid Zindashti for hits. But also here on how the reporter who alleged that bit of alleged news, was recently arrested by Turkey for disinformation and is being prosecuted.

It circles back to Vancouver because the issue, the thing that doesn’t fit the puzzle, is not two young gangsters who were murdered; but what did they know, or receive, that ties back to heroin, Turkish organized crime, Iran, the IRGC, or Iranian organized crime that no one wanted anyone in Canada to find out? It’s not Zindashti – we know it ties back to him – its something else, something more significant.

Maybe one day we will find out.

Postscript

Zindashti today

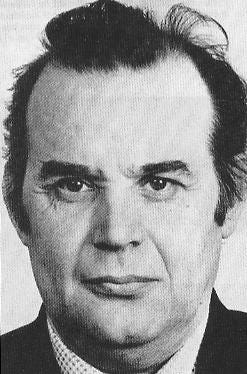

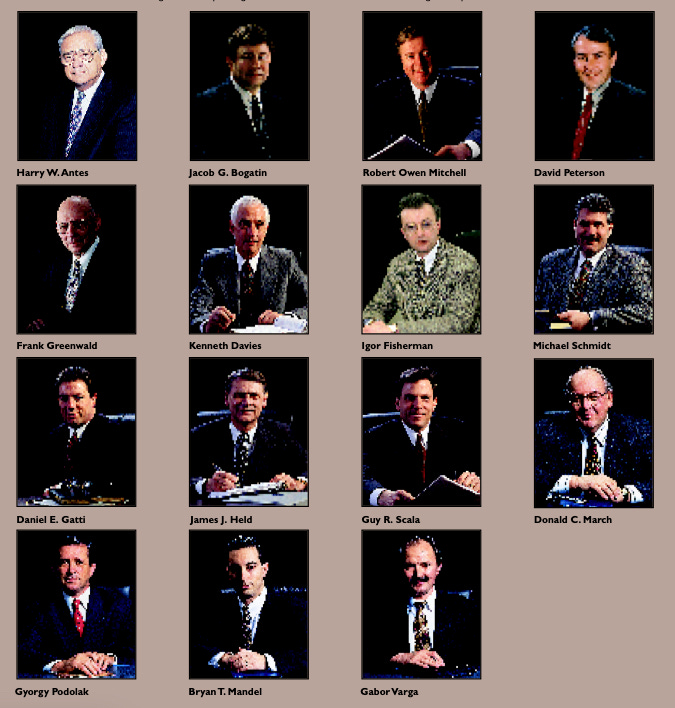

For all the heroin brought into Vancouver, these are the guys (below), who are sourcing it; who are at the top of that food chain; whom Vancouverites are funding.

Clip 1, below, is Zindashti in rural northern Iran. What is striking is the gun power, and expensive cars for that area.

Clip 2, below, is the funeral of Zindashti’s mother, and villagers are paying their respects to Zindashti because of the funeral (not in relation to any stature). The guns are less visible but you can see the large protection detail he has in Iran, and the body guards keeping villagers from getClip ting close to him.

Clip 3, below, is a series of videos where Zindashti was being received. Zindashti is wearing a black t-shirt; notice that Zindashti has a police vehicle escort, and notice from 0:22 to 0:24, the armed men in the background at the top of the mountain, guarding Zindashti.