How is Some Money Moved from China? Often with Smurfs and Structuring.

I am often asked how Chinese foreign nationals who have immigrated to the US, China, or EU, or are attempting to, move millions of dollars in funds to other countries unimpeded when there are Chinese banking regulations (commonly called currency controls) that prohibit the removal of funds from China above a certain threshold.

The answer is that often they use a scheme called “structuring”.

Structuring is a well-known technique in money laundering law. It involves breaking down large sums of money to get funds placed in the legitimate financial system to avoid anti-money laundering reporting requirements (usually in amounts just below $10,000). It is also called smurfing because often many people, that in the trade we call “smurfs”, work together to complete the placement stage, namely, they make small deposits to avoid detection that fall under the bank reporting threshold. Not all structuring involves proceeds of crime, but all structuring involves manipulating the movement of money through many different people to avoid detection and hide the true transactor behind the transaction. And all structuring triggers the requirement in the US, Canada and the EU to file a suspicious activity report.

Structuring is a Well-Known Money Laundering Method

Structuring by smurfs is such a well known method that all national laws in respect of money laundering take that into account by requiring that banks look at placements over a rolling 24-hour period specifically to capture smurfs smurfing the system with proceeds of crime. Other anti-money laundering legal provisions, including those dealing with third parties conducting transactions for others and the requirement to report suspicious activities such as structuring and use of third parties, are designed to identify and eliminate smurfing.

Criminals with proceeds of crime usually desire to move funds from one country to another, thus there is routinely an international wire transfer involved after placement (when all the smurfs have made their deposits) to quickly get the money exported and into the bank account the criminal has in another country. In China, politically exposed persons sometimes have proceeds of corruption that they want to remove quickly to a safe haven. Vancouver is sometimes viewed as a safe haven for Chinese foreign nationals who have proceeds of corruption. In anti-money laundering law, politically exposed persons (“PEP“) and private banking clients are both supposed to be given greater, not lesser, scrutiny.

How Structuring Is Used to Move Money

Let me give you a real example from a FBI case in the US that involved microstructuring. Microstructuring is structuring only with micro payments.

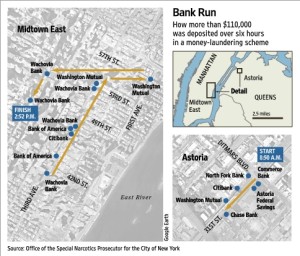

On March 15, 2006, in New York, Columbia drug lords ordered the microstructuring by smurfs of 112 deposits into several bank accounts. The drug traffickers in New York had to find a way to get the proceeds of drug trafficking to Columbia, so they decided to structure to avoid bank reporting requirements. The way it worked was that between 8:50am and 2:52pm, the drug trafficking smurfs in New York City made numerous cash deposits of US dollars in the range of $500 to $1,500 from drug trafficking revenues into banks all over Queens and Manhattan. In the space of a few hours, they deposited $110,000 in drug proceeds in various banks.

The Columbian drug cartel then used ATMs in Columbia to withdraw the funds in Pesos and the laundering cycle was complete. At the height of its activities, the cartel moved close to $2 million from New York to Columbia by microstructuring.

The Columbian drug cartel then used ATMs in Columbia to withdraw the funds in Pesos and the laundering cycle was complete. At the height of its activities, the cartel moved close to $2 million from New York to Columbia by microstructuring.

Structuring is Criminal

In 1986, structuring was criminalized in the US and in the year of this case, one office in New York alone indicted or convicted 25 people for the offence of microstructuring. The IMF estimates that between 2% and 5% of the world’s GDP — between $962 billion and $2.4 trillion is laundered worldwide every year. Authorities rely heavily on banks, which are required to report all cash transactions of $10,000 or more and to institute “know your customer” procedures to ferret out money laundering. Money laundering schemes are complex, employing layers of transactions, like structuring, to move money through multiple countries to obscure the trail of funds.

In China, structuring and the use of smurfs is as commonplace as in other jurisdictions only its most prevalent variety involves the skirting of Chinese banking laws that control the removal from China of more than $50,000 annually by Chinese citizens.

Structuring Scheme

In China, structuring is sometimes used.

Under a structuring scheme employed in China, a Chinese foreign national (who I’ll call the Evader) pays multiple smurfs (third parties) to use their bank accounts in China temporarily and file false bank remittance application forms.

The Evader transfers $50,000 into each smurf’s bank account in China. The smurf in China then completes a bank remittance application form to wire the $50,000 from China to Vancouver ostensibly for themselves as the declared remitter and “owner” of the funds, when it fact the funds are being remitted secretly for the Evader who is deliberately structuring multiple financial transactions using the global financial system to avoid detection.

The Evader locates and pays as many smurfs as are needed to act as the remitter of $50,000 to equal the amount she or he wants to export from China. The Evader has to pay each smurf a fee for agreeing to participate in the scheme.

Structuring can be a Money Laundering Conspiracy

Structuring schemes are well-planned and organized money laundering conspiracy (where it involves proceeds of crime), and can be a form of banking and government fraud in China, depending upon the circumstances. The conspiracy is to break the law and to abuse the international financial system to effect the removal from China of funds that are prohibited from removal by the person as a matter of Chinese policy. Those policy are in place to, inter alia, protect the Chinese economy and stop the enormous outflows of proceeds of corruption from China.

Structuring Hides Real Person Behind Financial Transactions

All structuring is designed to avoid detection of the real financial transaction that is occurring (the movement of a larger sum of money by one remitter, the Evader) by anti-money laundering compliance personnel and computer systems and to circumvent banking laws that protect our global financial system from financial crimes.

There is a litigation in Canada involving an employment matter which describes how a wealthy Chinese foreign national who immigrated to Vancouver structured many transactions through a Canadian bank. The judge in that case made a finding of fact that a Vancouver bank employee was aware of structuring from China by the client to avoid Chinese law, and facilitated the structuring activity.

The case is illustrative because it provides an example of a real case of structuring from China to Vancouver. In the case in question, the bank had a rich client who wanted to buy a luxury mansion in Vancouver for $5.7 million.

Chinese Banking Regulations Control Remittances

As noted above, banking regulations in China prohibit the removal of more than $50,000 annually by a person to any country, subject to some exceptions that require approval of the government. Chinese foreign nationals in China do not exercise the exceptions because they do not want the Government of China to be aware that they have wealth and that they intend to remove it from China to Canada.

According to the litigation case in question, the bank employee who was terminated, merged the wires into the Evader’s account so that the funds could be sent to a law firm as one transaction so that the wealthy Chinese foreign national who immigrated to Vancouver could pay the deposit for her mansion through her law firm. No one informed the law firm that its trust account was being used to receive structured funds.

Bank Employee who Apparently Ignored AML Law

In the litigation case in question, the judge explained that the wealthy foreign national from China needed ten different smurfs in China to send $50,000 each to ten other smurfs in Canada but could only find eight smurfs in Canada willing to accept $50,000 for her. In the middle of the night, hours before the deposit was due for her luxury Vancouver mansion, she called a bank employee and asked the bank employee to act as a Vancouver smurf to receive the funds. The employee thought there was nothing wrong with participating in a structuring scheme or allowing the bank to be used for that purpose, so she agreed.

The employee’s role, however, was disturbing from an AML compliance standard. The employee in question was well-versed in AML requirements because she was a licensed investment advisor and accountant, in addition to being a bank employee and had, in that sense, triple the AML reporting obligations. Despite that, she did not tell the bank about the incident and it is probably safe to assume that the employee likely did not file a suspicious transaction report for the structuring activity (part of which involved her bank account when she acted as a Vancouver receiving smurf), the use of third parties, and the activity to evade Chinese banking requirements.

In anti-money laundering law, a suspicious transaction that requires reporting includes a transaction conducted to conceal funds, inter alia, to evade any law or regulation, including a foreign one, or one that has no apparent lawful purpose.

No Lawful Purpose with Chinese Structuring Schemes

Structuring schemes are suspicious in the classic money laundering sense because they are designed for the sole purpose of evading banking laws and clearly have no lawful purpose in fact everyone knows its purpose is unlawful because that is the whole point, namely to unlawfully remove more than $50,000 from China by structuring to hide the fact that it is one person remitting the funds to Vancouver.