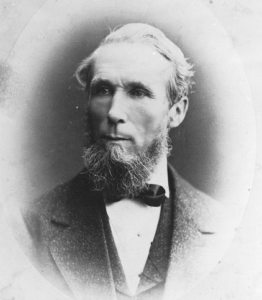

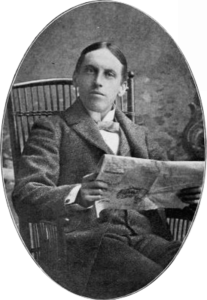

Jack

It was November 7, 1885.

John Worth Mitchell -Jack to his friends – was 8-years-old and living in Port Elgin, Ontario, when he heard from his parents that the unsinkable S.S. Algoma had shipwrecked and sank crossing Lake Superior.

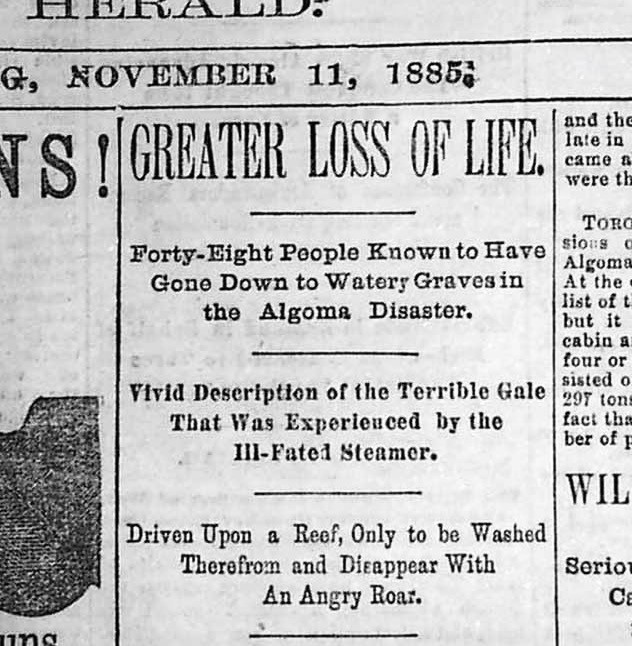

At least 48 passengers and crew had been washed away at sea and were presumed dead.

The ship’s voyage had started in Owen Sound, Ontario and many who lost their lives were from towns along Lake Huron.

Jack’s parents recognized two names among those who perished at sea – Edward Frost and Mary Jane Butchart.

Frost, Williams, Butchart

The Frost family was well known all around Ontario’s Bruce and Grey counties. Edward Frost was the son of John Frost and Mary Williams.

The Frosts were a prominent family in Owen Sound who owned a number of businesses. The Frosts were better known, though, as vocal abolitionists who operated the end point of the Underground Railroad in Owen Sound, sheltering former enslaved African Americans on the outskirts of town.

Edward’s Welsh mother, Mary Williams, left what must have been a life of luxury as the granddaughter of an Earl, and with her parents and three siblings, emigrated to Canada in 1817 and was one of the first European settlers in Bytown (now Ottawa). She married John Frost, from another Ottawa European settler family and in 1844, they moved to Owen Sound.

Mary Jane Butchart was the daughter of George McLauchlan Butchart, who had a business presence in Port Elgin and Owen Sound.

Edward and Mary were married in 1884 and had boarded the S.S. Algoma with their infant, Baby Butchart-Frost.

Jack didn’t know it then but he was fated to cross-over with both the Frost and Butchart families in the years to come.

His family and the Frost family would cross-over in marriage, and that cross-over would play an important role in the election of Margaret Thatcher, once the most powerful woman in the world; and he didn’t and couldn’t know either that he would eventually co-found and finance a portland cement company that became Butchart Gardens in Victoria, Canada.

Back then, he only knew that the child of two prominent families from the area had drowned in the worse shipwreck on Lake Superior, and so had its parents. He and many others along the Great Lakes wondered how the unsinkable ship had sank.

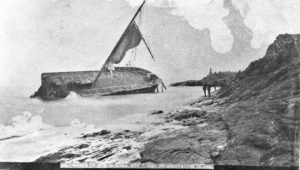

The unsinkable S.S. Algoma

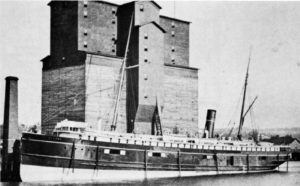

The S.S. Algoma was built in 1883 by the Canadian Pacific Railway. It was a luxury 263 foot steam ship that took passengers through Lakes Huron and Superior from Owen Sound to Port Arthur to connect with the railway to Toronto.

The Great Lakes had thousands of shipwrecks, especially in Lake Superior.

Knowing that, the S.S. Algoma had been built to be safe and unsinkable with many novel features for the era, including the first electric lighting on a vessel to eliminate fire hazards from oil lamps, the first steel hull in a Great Lakes vessel, and watertight compartments so that in the event of a collision, passengers would be safe from incoming water.

The S.S. Algoma was built in separable halves in Scotland so that it could travel across the Atlantic ocean to Canada in one piece under its own power. In Canada, it was then separated into two pieces and towed through the canals. It was then reassembled and the passenger compartments were built, before it continued its journey to Owen Sound, where it was put into service in May, 1884.

November 5th

On its fateful last trip, the S.S. Algoma left Owen Sound on November 5, 1885.

The highlight of the trip for passengers was passing through the locks at Sault Ste. Marie. Lake Superior is 21 feet higher than Lake Huron, and the Soo Locks elevate upbound vessels from Lake Huron to the height of Lake Superior so they can continue traveling the Great Lakes.

The next day, Nov. 6, 1885, the S.S. Algoma passed through the Weitzel Lock on time at 1 p.m. and then entered Lake Superior for the last leg of its journey.

The Frosts had their dinner and retired for the night.

November 7th

Halfway through Lake Superior, the ship ran into a blinding snow storm. The waves and the wind pumelled the ship for several hours as it made its way across the lake to Port Arthur. Soon, gale force winds and driving snow made it impossible to see much further than a few feet in the dark night.

By 4:30 a.m., the snow storm had turned violent.

Suddenly, passengers were thrown from their beds, woken by the searing sounds of the ship’s steel hull grinding over unyielding rock.

S.S. Algoma struck a reef

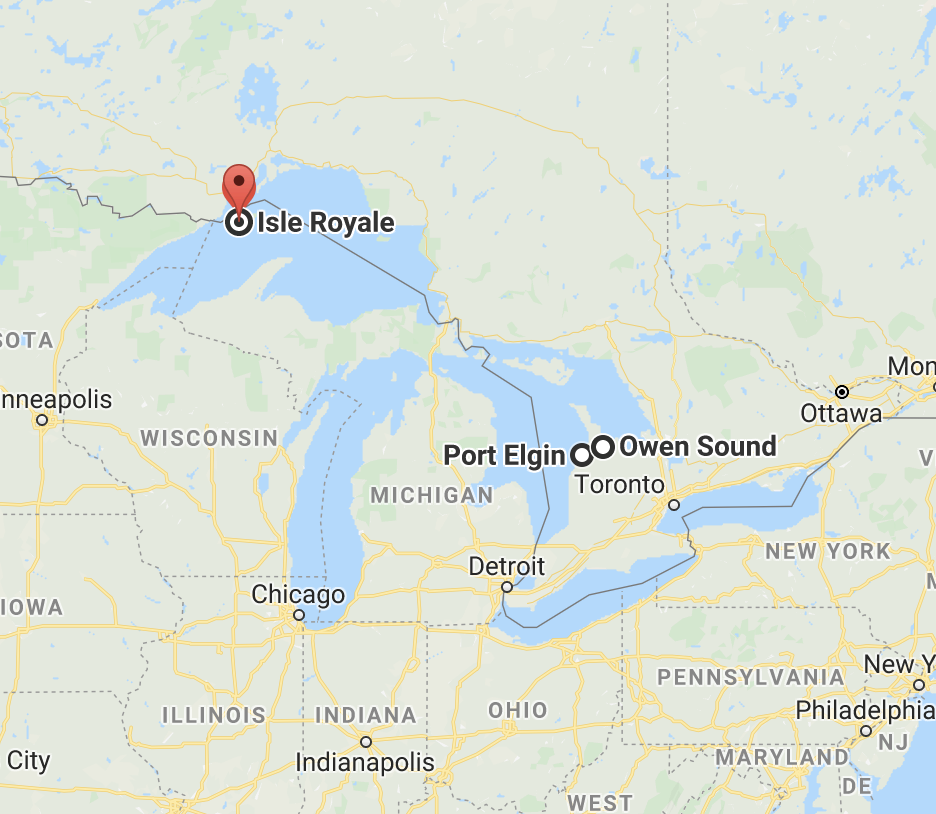

The S.S. Algoma had struck a reef off Isle Royale and started breaking up. Its rudder was broken.

The ship’s chief officer, Joseph Hastings, was stunned to see waves pouring in through the broken hull and washing away furnishings and parts of the forward ship.

He could hear the screams of women and children above the fury of the wind and the crashing waves.

Two sisters swept away

He started to make his way to the upper deck. Along the way, he found two young sisters sobbing in the ship’s saloon. They were wearing only nightdresses. The ship was swaying from side to side. He grabbed their hands and walked them forward, trying to steady them, battling the gale force winds, looking for shelter.

Just then, a wave smashed over one side and swept the sisters from his grasp and out to sea. He heard them scream until they were engulfed by the waves.

Hastings managed to make his way to the deck.

Passengers prayed for salvation

He saw passengers get down on their knees, and start loudly praying to God for their salvation.

The sea spared none of them – wave after wave washed them each away.

The ship’s purser, Alexander Mackenzie, was in the ship’s forward with the second officer and steward. They made an attempt to reach the other part of the ship to safety. The forward part of the ship broke off. Mackenzie was struck by a large wave and carried overboard. The forward portion of the ship disappeared into the icy waters.

Hastings and eleven other members of the crew gathered in the remaining part of the S.S. Algoma left afloat, wondering if the ship would hold; if they would be spared.

They were.

The next day, they made a makeshift raft and made their way to shore. They were rescued on Isle Royale.

Worst shipwreck on Lake Superior

In all, it is believed that 48 passengers and a handful of crew drowned at sea. It was the worst shipwreck in terms of loss of life on Lake Superior. The only passenger list was lost during the shipwreck. There was no way to confirm how many passengers were on board, leading to suggestions at the time that a hundred perished.

Parts of the S.S. Algoma sank that night and other parts were widely scattered along the lake and shoreline.

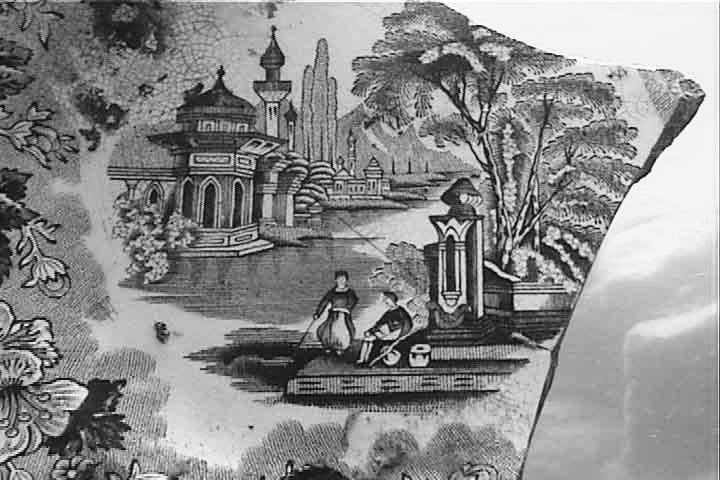

American fishermen recovered four bodies on the shore of Rock Harbour and reported that over 300 tons of freight, furniture, luggage, equipment, mail, a piano and barrels of brandy and beer were strewn about the rocky shore.

The body of Edward Frost was recovered among the rocks of Isle Royale. The bodies of Mary Jane Butchart and Baby Butchart-Frost were never recovered.

Prime Minister’s nephew

The purser who had perished when the ship’s forward washed away, Alexander Mackenzie, was the nephew of Canada’s 2nd Prime Minister (from 1873 to 1878), also named Alexander Mackenzie. Mackenzie demanded an inquiry immediately into the sinking of the unsinkable ship and got one. It was convened in Toronto. The great distance from Owen Sound to Toronto meant that none of the affected families could participate, give evidence or hear the testimony.

The inquiry heard that the S.S. Algoma had diverted miles off course during the storm and smashed into the reefs off Isle Royale at a speed of 16 miles per hour. On impact, it started to break apart at its centre seam – precisely into the two pieces that had been bulkheaded through the canal system to Owen Sound. The captain failed to assign a look out, even after visibility decreased. The inquiry held the captain negligent for having caused the loss of the S.S. Algoma and of 48 lives. His licence was suspended.

In 1885, CPR paid out $40,000 for claims of loss of cargo but the records indicate that it did not pay the families anything for the wrongful deaths.

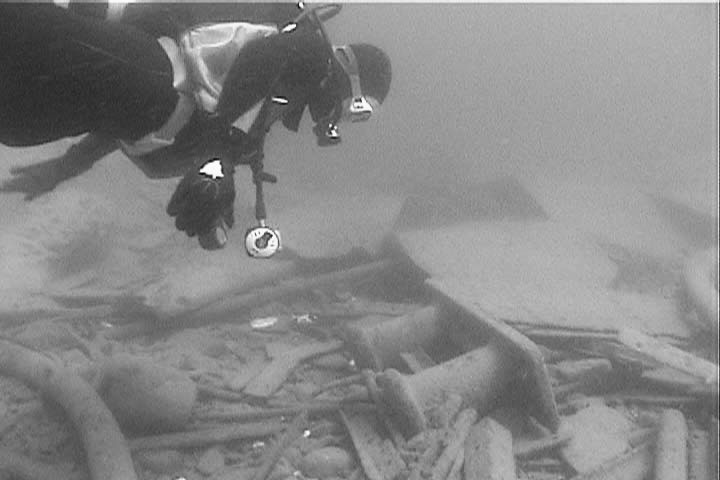

Shipwreck now a diving sanctuary

Today, the wreck of the S.S. Algoma is a scuba diving site off the coast of Michigan, administered by the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Among the wreckage, divers have found artifacts, dishes and the personal property of passengers, as well as some human remains of those who perished.

Fate

The tragedy of the S.S. Algoma impacted the lives of many in the Port Elgin and Owen Sound area.

One of them was James Alexander Tucker, an Owen Sound native who moved to Toronto to study at the University of Toronto. In Toronto, his inner circle included another (future) Prime Minister, William Lyon Mackenzie King. Tucker went on to become a writer, poet and magazine editor.

He wrote a poem about the shipwreck of the S.S. Algoma called Fate. It was published posthumously in 1903, by his best friend and then Saturday Night Magazine editor, Reuben Butchart.

In Fate, Turner wrote:

The white-fanged waves went snarling by,

When night had blown down from the northern sky,

On a hidden rock from the harbour far,

The ship plunged hard, and her tallest spar,

Sank where the bones of dead men lie,

When the sun rose, the ship and the men lay sunken there

Leading up to the turn of the century, Owen Sound Collegiate, a private high school in Owen Sound, had an unparalleled record for leadership and academic excellence among its students – students who crossed paths with each other later in Toronto.

Tucker was a turn of the century alumni of Owen Sound Collegiate. And so were Dr. Norman Bethune and Billy Bishop.

And so, too, was Jack.