Ponzi scheme is 101 years old

A lot has been written about Ponzi schemes, but did you know that the Ponzi scheme seems to have had its genesis in Canada? Since this December is the 101st anniversary of the conviction of Charles Ponzi, its probably a good time to explore the Canadian side of the world’s most famous securities fraudster.

Ponzi scheme defined

What is a Ponzi scheme?

There is no settled definition of a Ponzi scheme but the most relied upon definition is a financial fraud that induces investment by promising returns, usually in a short time period, from an allegedly legitimate business venture where proceeds from new investors are funnelled to previous investors from the alleged business venture, cultivating the illusion of legitimacy and inducing further investment (Donell v. Kowell, 533 F.3d 762 (9th Cir. 2008)). Ponzi schemes are presumptively insolvent from inception, as a matter of law.[1]

Carlo Ponzi immigrates to US

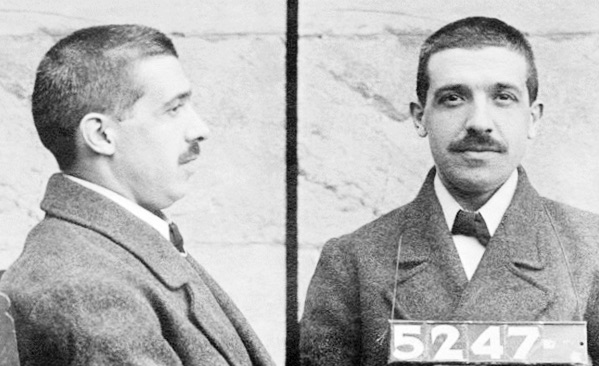

Charles Ponzi was born in 1882, in Italy as Carlo Pietro Giovanni Guglielmo Tebaldo Ponzi. He immigrated to the US in 1903, landing in Boston.

Once in the US, he moved from job to job, unable to stay with one employment for very long. Possibly as a sign of things to come, he was fired from a job as a waiter after he was caught shortchanging customers when they paid their bills.

Ponzi moves to Canada

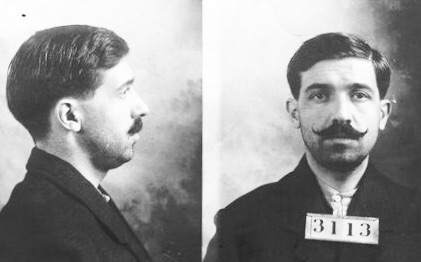

In 1907, he moved to Montreal, Canada, after learning that another Italian immigrant in Boston named Luigi Zarossi, had moved to Montreal and was running his own bank, the Banco Zarossi. Ponzi changed his name to Carlo Blanca, tracked down Zarossi in Montreal, and convinced him to give him a job as a teller at the bank. Ponzi was quickly promoted to bank manager.

Zarossi and Ponzi operated the bank more like an investment company than a deposit and savings institution. They solicited deposits from Italian immigrants, promising them 6% interest on deposits, when other banks were paying significantly less. They also offered remittance services to Italian immigrants, facilitating the sending of funds from Montreal to Italy.

Early Ponzi affinity-based fraud

The bank ostensibly grew as an increasing number of immigrant Italian customers opened accounts and left funds on deposit, but its growth and success was an illusion because instead of sending out remittances and managing customer deposits, the funds were going into Zarossi’s pocket. In the early days, when customers came to make withdrawals of their principal plus the 6% in promised returns, Zarossi and Ponzi repaid them with money from newer customers (the Ponzi scheme in operation). Word got around the Italian immigrant community that they made good on their promises and that generated more customer deposits into Banco Zarossi.

And thus Ponzi learned from Zarossi how to master what we now call affinity frauds, through existing social networks. In that case, the social network was the Italian immigrant community. By targeting Italian immigrants, Ponzi and Zarossi had instant trust and proximity to the victims. Ponzi also learned in Canada, how to master the type of fraud that would later bare his name.

All Ponzi schemes have to collapse at some point because of the fact that they are insolvent from inception and in 1908, the Banco Zarossi was collapsing because depositors could not be paid back. Zarossi took off to Mexico with a suitcase full of cash. Ponzi blamed Zarossi for the scheme and the disappearance of customer funds. One bank employee committed suicide and another disappeared, presumably killed.

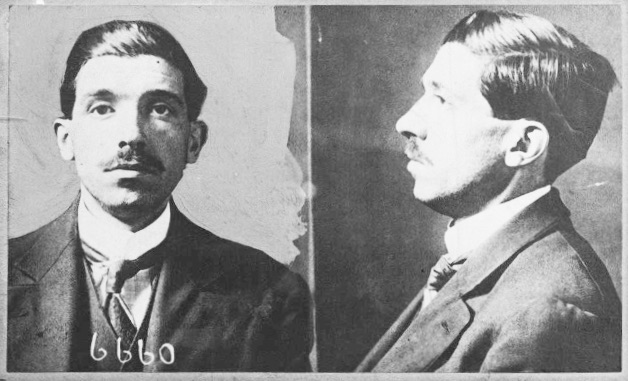

A few months later, Ponzi forged a cheque of a former customer of the bank, made out to himself using a third name, “Charles Ponsi”, and cashed it. He was caught and charged under that name.

He was convicted and sentenced to a term of incarceration of three years in Quebec, under another fake name, Charles Bianchi. While in prison, he wrote to his mother in Italy and explained that he was working as an assistant to a warden at a Canadian prison, hence his address at the St. Vincent-de-Paul prison.

In 1911, he was released from prison.

Ponzi returns to the US

That year, Ponzi decided to return to Boston and within a week of his release from prison, he crossed the border into the US with 5 Italians whom he was attempting to smuggle into the US illegally. He was charged, convicted and sentenced in the US to a term of incarceration of two years.

Ponzi was released after 25 months, and after his release, he took odd jobs for a number of years in New York City, Alabama and Florida.

In 1917, he returned to Boston and took a job as a store clerk. He met his future wife, Rose Gnecco, on a streetcar, and they were married in 1918. Ponzi took over a grocery business owned by his father-in-law and managed to run the business into the ground in less than a year.

Ponzi’s coupon scam

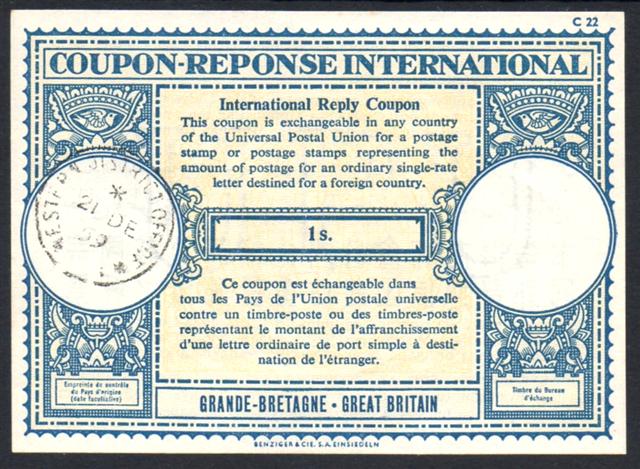

Broke, with mounting debts, Ponzi tweaked the Montreal formula pulled off with Zarossi and went into business for himself in Boston, selling Italian immigrants shares of a business (in the form of notes that evidenced the securities) that allegedly provided arbitrage opportunities over the discrepancy in prices of International Reply Coupons (“IRC“).

IRCs still exist – they are physical pieces of paper with a certain monetary value attached to each one – in the 1920s, the amount was about 5 cents.

Ponzi told investors that he was buying IRCs overseas and cashing them in the US, where the rates were better, making an alleged profit on each IRC purchased.

Ponzi promised investors a return of 50% in 90 days. When investors sought to cash out, Ponzi sweetened the deal to keep them on, promising them a 50% return in 45 days. Similar to the Montreal banking scam, he used money from new investors to pay out the old. The first few customers were paid back with the promised returns, to convince future investors that the scheme was legit.

Pulling in millions per week

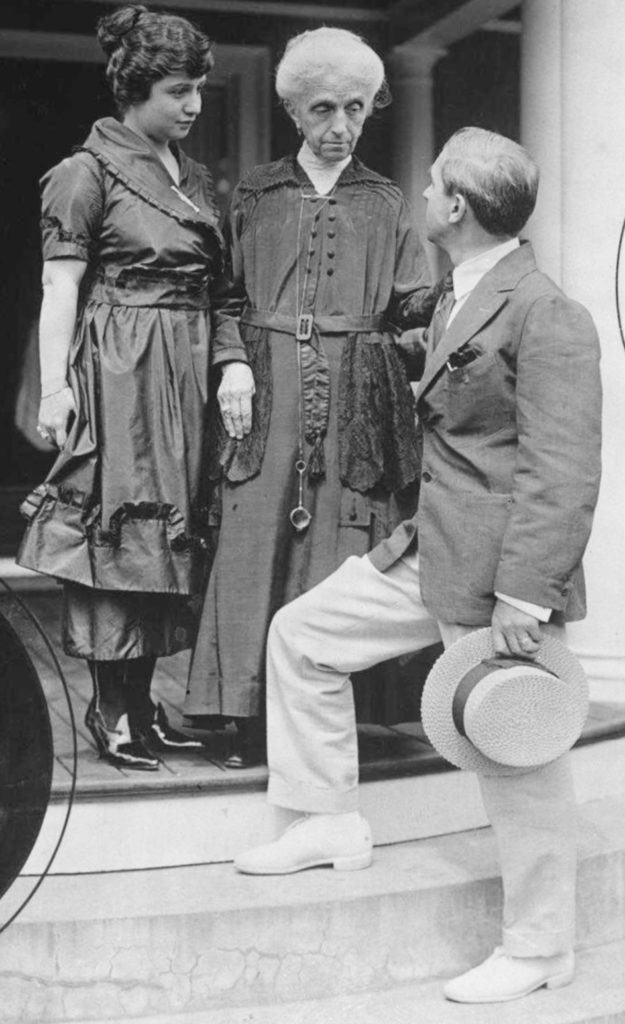

Ponzi was wildly successful luring in investors to give him money. By March 1920, people were lining-up down the street where his office was located, to drop off cash to invest. He was pulling in US$1 million per month. By June, 1920, he was pulling in US$1 million per week and was sitting on a fortune.

But it was a scam. For one thing, if the investments were legitimate, it meant that Ponzi was buying IRCs in Europe and having them shipped, physically, to the US where they would be cashed out. According to the US Postal Service, it would have required ships the size of the Titanic to be filled up with IRCs for it to be true. For another thing, it would have required a large number of employees and agents all across Europe to buy and ship the IRCs to the US, which Ponzi did not have.

Lavish lifestyle

As the money rolled in, Ponzi began to spend on a lavish lifestyle, moving to a 12-room mansion, buying luxury watches, the latest fashionable clothing, and luxury cars. The Boston Globe reported that he had a massive imported scotch collection in the cellar of his mansion that was worth more than the house itself. It could be that Ponzi intended to sell it, because in January 1920, the Volstead Act came into force, ushering in prohibition. In December 1920, however, when the receiver published the assets of Ponzi’s company and of Ponzi’s personal estate, the scotch collection was absent.

By July, 1920, Ponzi claimed to be worth US$8 million, about US$110 million today. He was so flush with cash, he bought a bank in Boston.

Then towards the end of July 1920, an investor in Boston filed a lawsuit for US$1 million against Ponzi, for an alleged debt and the Boston newspapers ran a story about it.

Run on the bank

That caused a flood of customers to visit Ponzi and ask for their money back, and for investigators to start to ask questions. There was a run on Ponzi’s company and the bank Ponzi acquired, for over a week during the first week of August.

During that time, Ponzi made numerous untrue statements to keep the con alive. For example, he fabricated a telegram to show a reporter that a fictitious bank in Canada called Levtur Canadian Bank, was sending him US$7,000,000. He did, however, pay investors who lined up back their principal during that first week but not without suggesting that they were going to lose out on big returns by cashing out early.

During the run on the money, Ponzi alleged that he had a secret winning formula to make money, and that a French organization had offered him US$10 million for his “secret”. He also informed investors and reporters that he had more than enough money in banks all over the US to pay every investor back.

His ego was not small for he once told the crowds swarming his office that he was the 3rd greatest Italian in the history of the world.

Ponzi arrested

On August 12, 1920, the Boston Globe revealed that Ponzi was a former convict from Canada, who was tied to a previous similar scheme at the Banco Zarossi in Montreal, and had been convicted in Canada and the US for various offences.

The next day, Ponzi was arrested. The US Attorney General’s early calculations estimated that he owed investors US$5 million, equal to US$40 million today.

Ponzi was charged with mail fraud.

After he was arrested and in order to deflect, Ponzi gave a certified statement to the Court alleging that a number of other people were responsible for the loss of investor funds, outright lying. The US Federal Court ruled, as a preliminary matter, that Ponzi was a one-man fraud show. Mr. Justice Morton called Ponzi’s statement blaming others for his actions “false and fraudulent”.

In the criminal complaint, the US federal government alleged that Ponzi falsely represented to investors that his company was in a position to repay them their investment funds whereas in truth, he was not in a position to repay each investor; it was also alleged that he fraudulently represented that he was in the business of trading in IRCs, which enabled his company to make large returns of profits, knowing that that was untrue.

On August 15, 1920, the Boston Globe published a story in which the US Postal Service was quoted as explaining that from 1907 to 1920, the value of all IRCs issued in the entire world was only US$1,349,235, and therefore Ponzi could not have bought US$5 million worth of IRCs and the scheme could not be legitimate.

Several banks collapsed in the aftermath of Ponzi’s arrest and tens of thousands of investors received only 30 cents for every dollar invested.

Ponzi was convicted on federal charges of mail fraud and later, he was convicted on state charges of fraud. He was released from jail in 1934, and deported to Italy.

How did Ponzi and Madoff do it?

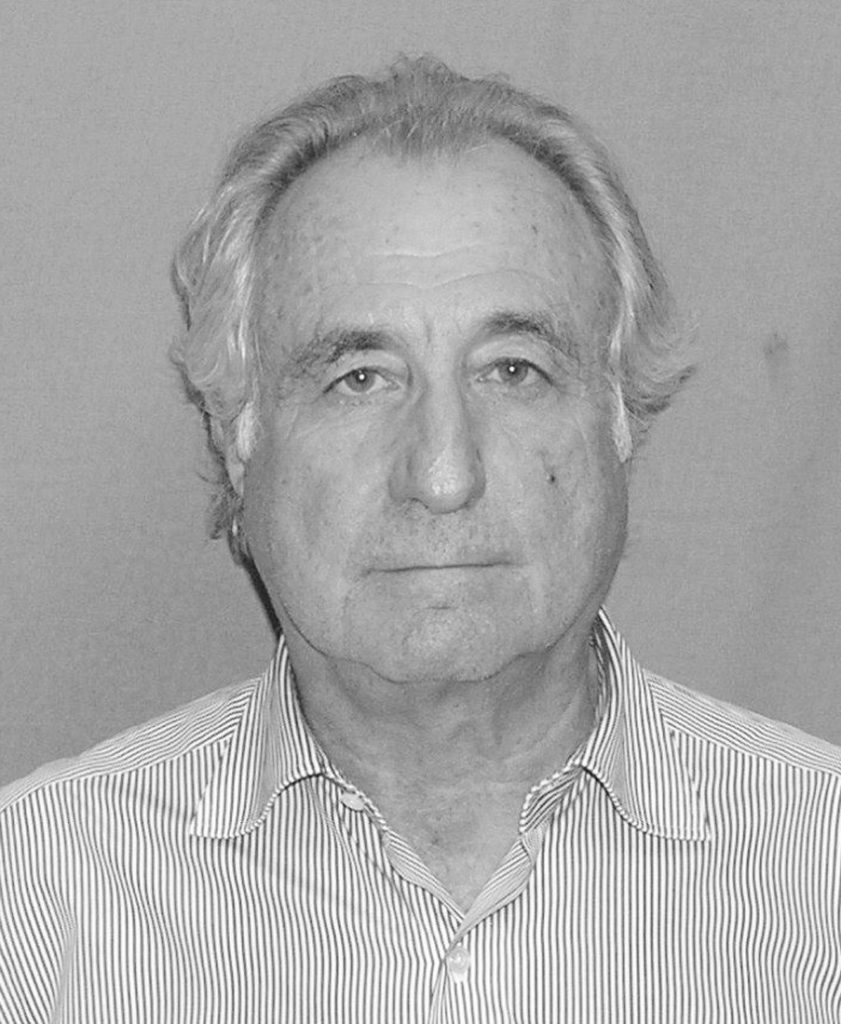

A number of academic studies in criminology have drawn parallels between Ponzi, Bernie Madoff and other Ponzi schemers to explain how come people fall victim to Ponzi schemes. Madoff was an American fraudster and financier who ran the largest Ponzi scheme in history, worth about US$64.8 billion in 2009.

Among the common features between Ponzi schemers, are that they are trust violators. They inspire trust among investors to such an extent that investors fail to apply rational decision-making or to conduct due diligence before investing, and then the fraudsters breach that trust.

Using social network analysis, academics have looked at the exploitative and deleterious effects of socially embedded networks and transactions used by Ponzi and Madoff, finding that both excelled at constructing and maintaining socially embedded networks for proximity between them and the victims, in essence perpetrating sophisticated affinity frauds.

Because this type of fraud is carried out through embedded networks, investor education programs advising investors to be weary of “too good to be true” investment schemes tend not to be effective.

Ponzi and Madoff both relied on culture, religious, social and family connections to launch their frauds, and those close knit groups remained oblivious that they were being defrauded until the very end.

The same is true of the Bulgarian-based OneCoin and the Canadian HabibiCoin founders from Montreal, both of whom used networks tied to Islamic finance and MLM techniques, and of Miami-based Scott Rothstein, who used the legal community, to run Ponzi schemes that were affinity-based. Finico, the alleged Ponzi scheme using Tether in Russia, is another recent example of using Islamic finance and affinity groups to scam investors.

Another well-known Ponzi scheme orchestrated by Sergey Mavrodi in Russia used affinity techniques to lure in poor investors en masse by projecting himself as the little guy against the state. In later iterations, Mavrodi (and those who continue his Ponzi scheme) used MLM techniques to lure in investors in Nigeria, India and Indonesia, and later, using the fake promise of the alleged financial freedom allegedly achievable by the fake Mavro Coin and Blockchain.

You can read about the Mavrodi scheme and its ICO iteration here, and watch their video promoting the Mavro Coin to investors on YouTube.

[1] A sine qua non of any Ponzi scheme is the repayment to one or more investors by the fraudster. To be a Ponzi scheme, the scheme must, therefore, have evidence of the manufacturing of returns to investors from other investors contributions. A fraudulent scheme that takes investor funds in violation of securities law, or which is a financial fraud with no legitimate business venture underlying the activities is not a Ponzi scheme if new investor funds are not used to issue “returns” or a payment to at least some investors.

The source of information in respect of Charles Ponzi was primarily from news articles published by the Boston Globe from 1920 – 1922, whose reporters interviewed Ponzi contemporaneously with the operation, end and prosecution of his Ponzi scheme.