The Champagne Trade That Moved Markets

The champagne was flowing at Cobalt 27’s Toronto headquarters on the evening of December 8, 2017.

The Canadian company had just executed a 720-ton cobalt purchase that spiked global prices by 10 percent overnight—a single transaction that jolted the commodity markets.

But the celebration wasn’t about shrewd trading. What they toasted as triumph masked something else entirely.

That champagne trade removed just 1.7% of visible cobalt inventory—yet prices jumped 10 percent overnight. That’s a short-term price elasticity of 5.9x, meaning prices rose nearly six times faster than the supply fell. In a normal commodity market, a 1.7% drop might move prices by 1 percent—not cause a surge.

No one in Canada noticed. But in Shanghai, analysts took note.

Just days after the trade, Guojin Securities published an investor note on Cobalt 27, warning investors to focus on “high-quality companies,” and recommending Huayou Cobalt and Hanrui Cobalt.1 In Chinese research culture, that was not a subtle message.

Guotai Junan’s Nonferrous Metals team also flagged market anomalies. In a retrospective, they concluded that Cobalt 27 had been buying and hoarded cobalt to raise prices.2

Behind it all, they wrote, was the “white glove”3 (白手套 which means a front or proxy) of Pala Investments, using the public vehicle to “pull up cobalt prices.”4 Guotai called it a “classic case of commodity financialization.”5

Cobalt 27 was, in the words of co-creator Michael Beck, “constructed [as a] pure cobalt play—if the cobalt price is up, Cobalt 27 share price is up; if the cobalt price is down, it’s down.”6 The champagne trade delivered as designed: the price spike lifted the stock.

But as everyone in the capital markets knows, an artificially inflated price can only be sustained for so long. If you remove what is supporting it, the market adjusts down.

That’s exactly what Guojin warned in December, just days after the champagne trade—predicting that prices would “experience a significant drop”7 when Cobalt 27 stopped acquiring and hoarding cobalt.

The reckoning came.

When Cobalt 27 stopped buying, cobalt prices collapsed by 50%, and the company’s share price plunged from $14 to $5.72—a crash foretold back in 2017, by the analysts in Shanghai who’d seen past the champagne haze.

Descent into Sedarland

The champagne trade only makes sense when you see how Cobalt 27 was built—through a maneuver so common in Canadian markets it barely raises eyebrows: find a shell, take it over, and rebuild it as something new.

The company’s foundations were laid months (if not years) earlier in a peculiar IPO. More than half the offering wasn’t a capital raise at all—it was a modern-day barter, with public shares exchanged for raw cobalt.

Some of the barter counterparties who did deals with Cobalt 27 read like a casting call for a financial thriller:

- An 80-year-old Oregon doctor who bartered enough cobalt to fill three Boeing 737 cargo planes—from his gated retirement community.

- A shell company sharing an address with Voyager Digital, incorporated days before a $44 million cobalt deal—a volume equivalent in weight to 112 African elephants.

Barter deals are strange in any IPO. But here, some cobalt came from the company’s own founders—who bartered it back at prices they helped set.

To understand how it worked—and who benefitted—we need to descend into Sedarland.

Previously, in Smoke and Mirrors

To recap: Part 1 introduced the three Vancouver-listed issuers at the heart of this series—Cobalt 27, Nickel 28, and Blockmint Technologies—and followed an opaque syndicate of characters.

We began with Cobalt 27, launched in 2017 and pitched by promoter Michael Beck as a “cobalt ETF on steroids” for investors hoping to ride the electric vehicle boom. Within two years, the company had raised hundreds of millions, gone public, gone private, and returned to the control of the Russian oligarch from whence it had emerged.

In Part 2, we followed that oligarch—Vladimir Iorich—from the coalfields of Siberia into the inner circle of Marc Rich, tracing his ascent through Mechel and its 2008 merger with Oriel Resources PLC.

From Oriel, some of the same actors went on to form Uramin, another Canadian mining venture. Uramin, acquired by France’s Areva in a $2.5 billion debacle, was denounced in the French press as “une énorme escroquerie” (CNEWS), “une gigantesque escroquerie” (Libération), and simply “une escroquerie” by state broadcaster Radio France.8 Canadian Senator Céline Hervieux-Payette put it another way: in the Senate, she called Uramin the work of “the Dattels gang.”9

After Oriel and Uramin, some of these same individuals resurfaced in Cobalt 27, alongside Iorich, as yet another murky Russian-Canadian deal took shape on the TSX Venture Exchange.

Building the Cobalt Shell in Canada

Before the IPO, Cobalt 27 was a dormant British Columbia shell called Arak Resources. Through a four-part corporate reconstruction documented in Sedar, the shell was reassembled into a cobalt-holding vehicle.

Phase 1: Shrink the Float

On October 3, 2016, Arak Resources announced a 10-for-1 share consolidation, cutting its public float from 12,201,269 shares to just 1,220,126.

Phase 2: Assemble the Founders

On February 14, 2017, Arak announced plans to raise $650,020 through the sale of 4,643,000 units at $0.14 apiece. Each unit consisted of one share and one warrant. The company also disclosed a strikingly high 20 percent finder’s fee—paid in a mix of cash and securities—for sourcing the investment.

Phase 3: Inflate the Float

On March 20, 2017, Arak said the financing had closed. It claimed to have sold 4,634,000 units—not the announced 4,643,000—yet still reported gross proceeds of $650,020. The math didn’t check out: 4,634,000 units at $0.14 each equals $648,760.

The finder’s fee was paid to NewGen Equity Long-Short Fund, managed by David Dattels, the son of Stephen Dattels. Arak specifically said he was not a connected party.

In its attorney’s filing, the company said NewGen received only warrants. That was false. NewGen received 300,000 units.

Following the financing, Arak had 6,154,126 shares issued and outstanding. This meant the new investor group—the soon-to-be founders of Cobalt 27—controlled at least 80 percent of the company, though the filings omitted ownership breakdowns

Sedarland Math

Between April 3 and April 10, 2017, Arak issued news releases, material change reports, and interim filings, none of which fully reconciled.

One material change report stated the company had 11,016,127 shares outstanding, a number only possible if 4,853,001 warrants had been exercised during the hold period. Elsewhere, Arak claimed 4,898,000 warrants had been exercised, raising $881,640—roughly $8,100 more than the share count could support.

In the same week, Arak’s MD&A contradicted both, stating that 11,061,127 shares were outstanding—a figure that matched the 4,898,000 warrants but conflicted with earlier filings.

All of those filings can’t be true at once.

In a matter of months, Arak had consolidated 12 million shares down to 1.2 million, then re-inflated the number back to 11 million. That made no sense unless the goal was to swap out who held the most shares. The rollback cleared out the old shareholder base. The private placement installed a new one.

It was, in substance, a change of control. You just wouldn’t know it from anything in the filings.

Maybe that was the point.

Phase 4: The Transformation

The Mickey Mouse–level disclosure continued.

On April 10, 2017, Arak completed its metamorphosis and renamed itself Cobalt 27 Capital Corp. It issued a backdated news release announcing a 3-for-1 stock split.

Even this final step was bungled.

- One filing stated the split would produce 33,048,381 shares.

- The company’s auditor bumped that figure to 33,183,280.

- And let’s go for a third contradiction: in another filing, the company stated the split would produce 33,183,381 shares.

That’s 135,000 shares unexplained, worth over $1.2 million at IPO.

The transformation was complete. A dormant shell company had been reborn as the vehicle for one of the most unusual IPOs in Canadian market history.

Known and Potential Founders

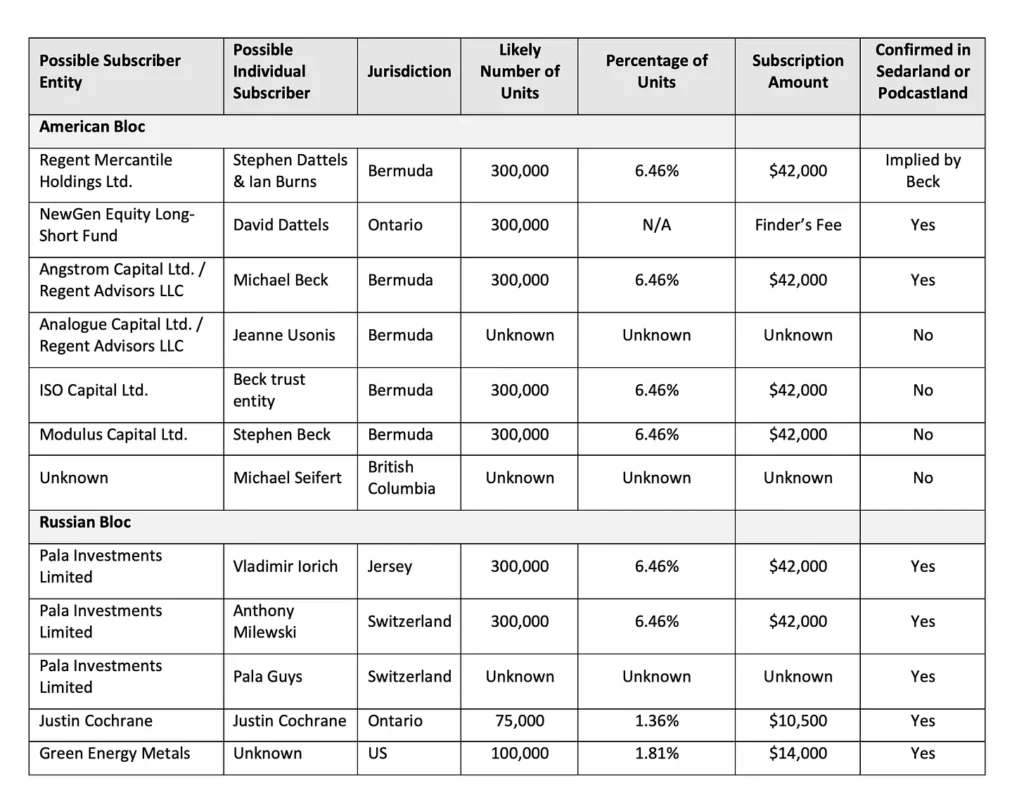

Three days later, Cobalt 27 filed its exempt distribution report for its March private placement, listing 27 anonymous investors. While no names were disclosed, surrounding filings and historical affiliations suggest that the participants may have clustered into two blocs—one orbiting Michael Beck, the other around Vladimir Iorich.10

First Bloc

The first bloc may have included:

- Stephen Dattels and Ian Burns (Regent Mercantile Holdings Ltd.).

- Michael Beck (Regent Advisors LLC and Angstrom Capital Ltd.), founder and consultant to the company.11

- Jeanne Usonis (Regent Advisors LLC and Analogue Capital Ltd.).12

- Michael Seifert.13

Second Bloc

The second bloc may have included:

- Anthony Milewski (Pala Investments Limited), founder, and CEO.14

- Undisclosed “Pala Guys.”15

- Vladimir Iorich (Pala Investments), founder, major backer, and cobalt barter counterparty.16

- Justin Cochrane, founder, President, and COO.

- Green Energy Metals Fund, pre-IPO warrant holder, consultant to the company, and cobalt barter counterparty.17

The table below represents a reconstruction based on filings, subscription amounts, jurisdictions, and known affiliations. Individuals and entities not disclosed in Sedarland or Podcastland, are inferred from patterns observed in other issuers.

If the reconstruction holds—and it may not—these appear to be the subscribers who built Cobalt 27 from the shell of Arak.

There’s nothing improper about joining forces to launch a cobalt vehicle. The issue is that not a scintilla of their syndication appeared in Sedarland.

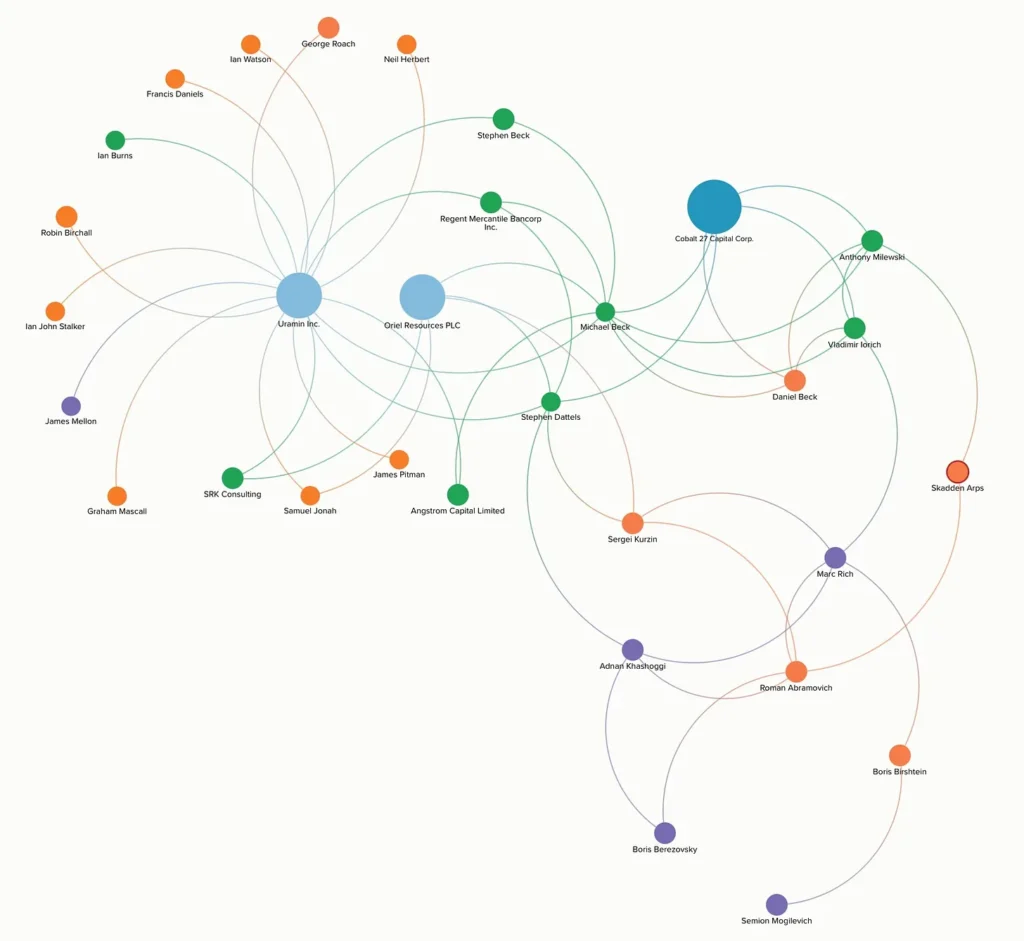

The diagram below offers a partial map of relationships among individuals and entities tied to Cobalt 27, Oriel Resources, Uramin, and related ventures. It draws from Sedarland filings, public company disclosures, and corporate records across jurisdictions.

This map is not exhaustive. It emphasizes recurring actors, overlapping company roles, and patterns, some dating back more than a decade. As the series continues, we’ll expand it to include Nickel 28, Blockmint Technologies, and others in the recurring cast.

Mickey Mouse Governance

With the founder shares locked in, Cobalt 27 executed a flurry of contracts over just four days, including for its executive team:

April 18: The company hired Marrelli Support Services to provide CFO services at $2,500 per month. The decision would prove prophetic—Marrelli would later serve as CFO for Voyager Digital, the cryptocurrency exchange that famously collapsed, in yet another connection to Voyager Digital.

April 20: Cobalt 27 signed a $250,000 per-year contract with Anthony Milewski for part-time “corporate development” services, even though he was a managing director at Pala Investments, the firm controlled by Vladimir Iorich, one of Cobalt 27’s founding shareholders. According to the contract, Milewski reported to no one—not even to the board. There was, in fact, no reporting structure at all in his contract. For the first 11 days of part-time corporate development work, Cobalt 27 paid Milewski $67,690, which was 798 percent more than the contract allowed.

April 21: A parallel part-time “corporate development” contract was executed with Justin Cochrane at $10,000 per month, mirroring Milewski’s reporting structure with Cochrane also accountable to no one. Remarkably, this contract was signed by Milewski, who listed his role as “Chairman and CEO”—exactly one day after being hired for part-time corporate development work. So was he doing part-time corporate development or acting as CEO?

The same day, another company document listed Cochrane as affiliated with Arlington Group Asset Management Limited, a London firm that Cobalt 27 hired as an “independent” advisor. So was Cochrane working for Arlington, Pala, or Cobalt 27? Or all three?

April 21: The company executed a royalty agreement to pay $300,000 in shares to Asian Mineral Resources, a company 74 percent owned by Pala Investments. This transaction was not disclosed as a related-party deal. The royalty covered a Vietnamese mine that had been mothballed on care and maintenance since 2016, providing no discernible benefit to Cobalt 27 shareholders.

Then things got more convoluted.

Just three days after being hired as part-time corporate development consultants, Milewski and Cochrane were reverse-promoted to CEO and COO, respectively—although when and how, exactly, depends on which filing you read.

One announcement stated Milewski was appointed Chairman and CEO on April 20, 2017. Yet on the same day, he signed his contract demoting himself to corporate development work—a contract that, by its own terms, superseded all prior agreements.

Disclosure around Cochrane was no better. One document claimed he had been an officer since March 31, 2017. Yet on April 21, one day after his supposed promotion, he too signed a contract demoting himself to part-time corporate development tasks, which also superseded all prior agreements.

Taken at face value, the filings show executives were hired, promoted, and then demoted in that order.18

Mickey Mouse governance, top to bottom.

Once-in-a-Lifetime Opportunity

With a rented CFO and two freshly demoted part-time consultants at the helm, Cobalt 27 announced its debut as a cobalt company.

The Cobalt 27 pitch hinged on three core claims:

- The share price was tied to physical cobalt.

- A looming global cobalt shortage from China for EVs would create significant upside.

- The company would hold the second-largest stockpile of raw cobalt in the world.

The idea was that when cobalt shortages hit, buyers in China, which was 80% of the market, would turn to Cobalt 27, driving up demand—and by extension, the share price.

Cobalt 27 promoter Michael Beck, made the case this way:

“So the world, the next 7 years is going to have to increase cobalt production by 350 percent,” he said, emphasizing that cobalt is “only produced as a by-product, and two-thirds of which comes from the Congo.”

“You can imagine many scenarios where that doesn’t happen,” he added, “and the consequence is the price—because of the price inelasticity—goes really crazy.”19

To illustrate, Beck cited Tesla’s Model 3, which he said was being produced at 500,000 units per year, and each required 8 kg of cobalt—though he rounded it up to 10 kg “to keep the math simple.” That single Tesla model, he claimed, would generate demand for 5 percent of global cobalt supply. He then pointed to Volkswagen’s goal of 30% EV sales by 2025 as further evidence of exploding demand.

“We think cobalt’s really interesting … it’s one of these once-in-a-lifetime sort of metal events for investors.”20

The “we” was presumably he and Stephen Dattels, whom he identified as his longtime partner in a metals acquisition investment strategy.

Some of Beck’s claims about Cobalt 27 were inaccurate:

- Cobalt production was not on track to triple. By 2023, it had only risen about 50 percent since 2018—nowhere near Beck’s forecast of 350 percent.

- Tesla’s Model 3 used 4–5 kg of cobalt, not 8, and certainly not 10—placing actual demand closer to 2 percent, not 5 percent.

- While Volkswagen did expand its EV offerings, it relied primarily on LFP batteries, which contain no cobalt.

- His “once-in-a-lifetime” promise came not at the peak, but after cobalt prices had already dropped nearly 40 percent from their 2018 high.

And the “once-in-a-lifetime” opportunity—was that true?

For founders, yes. For ordinary investors, no.

Having bought in at $0.14 per share, if insiders exited right after the IPO, their return was a phenomenal 6,328 percent. If they exited in March 2018, their return was even higher—9,542 percent.

But for any retail investor buying at the IPO level—only to be taken out at Pala’s privatization price of $3.57 per Cobalt 27 share—the return was a dismal negative 60 percent.

The $200 Million Half Barter IPO

Three Prospectuses

Behind the once-in-a-lifetime pitch was the hybrid IPO.

While announcing its pop-in executives, Cobalt 27 also announced a $200 million financing. The filings called it an IPO. But half the shares weren’t sold. They were bartered for cobalt. The cash raised? Mostly earmarked to buy even more metal.

At first glance, it made little sense. Why would anyone buy cobalt and barter it back for shares? Acquiring and storing physical cobalt required millions in hazmat-grade logistics—plus insurance, warehousing, and transportation. And at the IPO’s valuation, the economics didn’t work.

This made the prospectuses critical—not just to explain the financing and its economics, but to disclose the risks. Here, the risks were heightened because the company was swapping stock for opaque, illiquid physical commodities, and transparency was supposed to be key.

Even Cochrane acknowledged this. He described the cobalt market as “opaque,” unlike, he said, pricing for more liquid metals like gold or silver.21

Point taken. The market was opaque. The risks were real.

Prospectus 1

The first prospectus, dated April 21, 2017, landed in Sedarland alongside a news release.

In it, Cobalt 27 disclosed it had signed 13 material cobalt contracts tied to its IPO—some structured as share-for-cobalt barter deals, others to be paid for in cash using the offering’s proceeds.

The company represented to investors that “all” of its cobalt contracts were “arm’s length.” That was odd, considering its CEO was simultaneously on the payroll at Pala—one of the largest cobalt barter counterparties in the IPO.

The news release announced two part-time hires from Pala Investments—Vladimir Iorich’s firm—bringing the number of “Pala Guys” moonlighting at Cobalt 27 to at least four. That included Milewski and Iorich, both already founder shareholders.

Robert Mitchell of Green Energy Metals was also hired. Meanwhile, Arlington Group was brought on as an “independent” advisor—despite its potential ties to Justin Cochrane.

The prospectus did disclose a conflict for Milewski, noting he held roles at both Pala and Cobalt 27, and that Cobalt 27 had agreed to barter cobalt with Pala and accept a cash subscription from it. But the framing—and especially the omissions—suggested Pala was a new investor, entirely leaving out that it already held 5.42 percent of the shares and had joined the March 2017 private placement as a founder. Those pre-existing founder shares were not disclosed anywhere in the prospectus.22

More importantly, why acknowledge Milewski’s conflict and not Iorich’s? Iorich was Milewski’s boss, controlled Pala, and Pala held equity in Cobalt 27. That dual role arguably required disclosure too. And if both were insiders at Pala, why wasn’t their combined shareholding of over 10 percent disclosed? Beck had said some “Pala Guys” helped start Cobalt 27. So where were their shares?

After Cobalt 27 was privatized, Milewski made a telling comment:

“I would say it’s a really interesting thing about Cobalt 27, and Pala Investments—they were that long-term capital. I think no one ever noticed that those guys participated in every single financing.”23

“Every single financing” includes the March 2017 private placement where the founders were assembled.

It’s no wonder “no one ever noticed”—because no one was ever told. The prospectus omitted that Pala held pre-IPO shares, and was, as Milewski stated, a founding investor by virtue of being in the March financing.

Another omission: Cochrane’s work history. The prospectus left out what he was doing from December 2015 to the IPO in June 2017. But as explained in Podcastland, we know what he was doing—just not where. He was putting the pieces together for Cobalt 27 while it was still a Pala project.24

Meanwhile, Michael Beck presumably held founder shares as its co-creator and was, or would soon become, a paid consultant through Regent Advisors LLC. Yet he wasn’t named anywhere in the prospectus. Nor were his shareholdings. His presence only emerged through outside sources, who described him to us as ever-present in early meetings, always accompanied by Michael Seifert, who reappears in Blockmint and Voyager Digital.

One more wrinkle: Daniel Beck, associated with Michael Beck, also worked at Pala and appeared tied to Cobalt 27. Was he a fifth Pala Guy?

By now, the cast had taken on a family-like structure—the Beck Family, the Dattels Family, the Pala Family.

Prospectus 2

The second prospectus dropped in Sedarland on May 30, 2017, alongside an investor deck.

It revealed that the majority of the IPO would consist of bartered shares. Cobalt 27 planned to barter 9,983,543 shares for 1,254.9 MT of cobalt. An additional 902.6 MT would be purchased with cash, amounting to a cobalt shopping spree. Altogether, the company projected $171.8 million in cobalt holdings.

Cobalt 27’s investor deck made representations and warranties to investors that they had a “transparent plan,” a “low-cost structure,” and fiscal discipline, claiming annual expenses would be capped at $2 million—lower than peers, it promised.

Those representations and warranties would prove wildly untrue.

Within six months of the IPO, Cobalt 27’s auditor reported $10.36 million in operating expenses—implying an annual run rate of over $20 million. That was 10 times the promised $2 million cap, and 12 times the advertised 0.9 percent expense ratio.

The same financials disclosed $3 million in fees paid to an unnamed advisor for the IPO. Someone got $3 million for 60 days of work—who was it?

The second prospectus listed 18 material cobalt contracts, adding five new ones, including:

- Pala Investments Limited.

- Green Energy Metals.

- Robert Mitchell.

- Justin Kurland.

Several of these counterparties were not at arm’s length.

Pala Investments clearly wasn’t. As noted earlier, it was a founding shareholder, held 5.42 percent of Cobalt 27, and its managing director, Anthony Milewski, served as Cobalt 27’s CEO—and was a founder too, with an equivalent 5.42 percent of the shares.

Green Energy Metals was tied to Robert Mitchell, who had just been hired by Cobalt 27 in a part-time capacity. It too was not arm’s length. Green Energy also held pre-IPO warrants, suggesting it was a founding shareholder.

Justin Kurland, who would later resurface at Blockmint alongside Pala’s Daniel Beck, was a trader at Green Energy.

Yet aside from a brief acknowledgment of Pala’s conflict via Milewski, the prospectus made no meaningful disclosure to inform investors that these were potential related-party transactions—or that key counterparties had overlapping relationships with the issuer. The prospectus also failed to disclose that these four parties accounted for nearly half—48 percent—of Cobalt 27’s supply chain. Most of the cobalt acquired, whether by cash or shares, came from them.

Prospectus 3

The final prospectus in Sedarland, dated June 16, arrived alongside another news release and additional filings.

It re-listed the 18 material cobalt contracts. One was dropped and replaced with another: Fargo Metals, a Delaware entity. There was a curious connection to Voyager Digital—Fargo Metals shared the same address. In other words, this shell—registered at what would later share the same address of a crypto disaster—received $44.2 million from Cobalt 27 under the IPO.

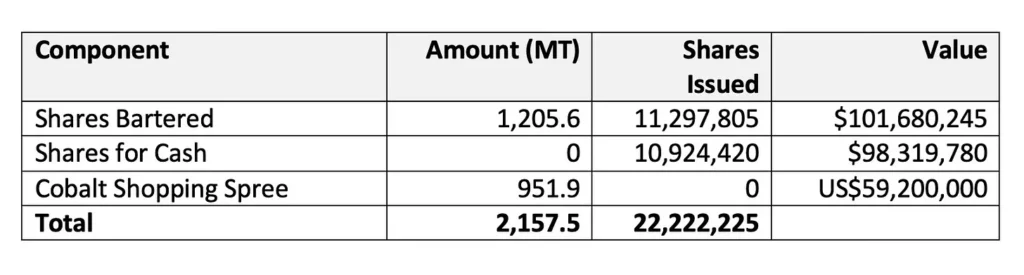

On financing, the prospectus clarified how the three-part offering would close:

Shares-for-Barter: 1,205.6 MT of cobalt, valued at $101.7 million, was bartered for 11,297,805 shares—representing 50.84 percent of the IPO.

Public Cash Offering: $98.3 million was raised through a share sale to the public, resulting in the issuance of 10,924,420 shares to a syndicate of underwriters.

Cobalt Shopping Spree: $78.5 million of the cash raised was immediately used to purchase approximately 950 MT of additional cobalt.

Remarkably, in fact astoundingly, although more than half the IPO was a barter scheme, hundreds of pages of disclosure in Sedarland entirely avoided using the word “barter.” It’s like writing a cookbook without ever using the word “recipe”.

Compared to the May filing, the total value of cobalt purchased and bartered increased by 4.6 percent—suggesting cobalt prices had risen that much in just 16 days, even though there was no obvious global shift in cobalt supply or demand.

In this prospectus, as well as the one before it and in subsequent disclosures like the AIF, Cobalt 27 repeatedly claimed that its cobalt was, and would remain, stored in warehouses on a segregated basis—“and not co-mingled with any other party’s cobalt.”

Yet on the very day that assurance first appeared, Cobalt 27 published its investor deck containing a photograph of Nikkelverk-branded cobalt drums stacked in slats, visibly grouped with drums marked “GEM”—presumably Green Energy Metals, below.

In other words, on the very day the company assured investors there would be no co-mingling, it released a photo that appeared to show exactly that.

Then, in July 2018, Cobalt 27 reported it had been the victim of a cobalt heist in Rotterdam. According to the company, bandits had made off with 112 metric tons of cobalt—an entire warehouse of drums.

But here’s the issue: the company’s auditor later reported that nearly one-third of the cobalt stored at that location—32.14 percent—didn’t actually belong to Cobalt 27.

It was someone else’s. It was co-mingled!

As with the Arak shell, share count was still something they were bungling. After extensive due diligence, the IPO underwriters confirmed Cobalt 27 had 1,659,169 shares issued and outstanding as of June 16. That meant that a 20-to-1 share consolidation approved by the directors in May had taken place.

But the auditor later reported that the consolidation occurred on June 23, and the post-consolidation number was 1,659,164 shares—not 1,659,169.

With underwriters, attorneys, and auditors all combing through the deal, one might expect alignment on such basic facts. Instead, they contradicted each other on both the timing and the math. For a nine-figure public offering, it was revealing.

In eight months, the game of musical chairs with the share count went like this:

- 12 million to 1.2 million.

- 1.2 million to 11 million.

- 11 million to 33 million.

- 33 million to 1.6 million.

- 1.6 million to 22 million.

Another remarkable revelation: 79 percent of the IPO proceeds were gone at closing—spent on the cobalt shopping spree. It may have been a record-breaking IPO burn. Of the $200 million raised, just $19 million remained.

But that, supposedly, was fine. According to the company, annual expenses wouldn’t exceed $2 million. It only had a few moonlighters and three inexpensive executives running the operation “from an Excel spreadsheet.”25 It could last for years without raising another dime.

And investors had nothing to worry about. As Michael Beck put it, they simply had to stick Cobalt 27 stock in a desk drawer, and because it was a “once in a lifetime” event, “go to sleep and wait for the cobalt prize.”26

The Barter Absurdity

Bartering Shares: Legality, Optics, and Absurdity

Cobalt 27’s scheme—bartering shares for cobalt—may sound like something out of a medieval market stall, but it is, in fact, legal under Canadian and U.S. securities law. The conditions are straightforward: the goods must be fairly valued, disclosed properly, and the barters treated equally.

In theory, any public company can issue equity bartered for physical goods. But this type of financing presents at least three serious challenges:

- Valuation: If IBM decided to issue shares bartered for diamond rings from grandma’s jewelry box, how would it ensure that Mary’s ring—bartered for 10 shares—was worth the same as Paula’s?

- Verification: How do regulators verify that the rings existed, and changed hands?

- Optics: It reads more Tehran bazaar than Bay Street. Let’s be honest, IBM would never barter its shares away.

To this day in Sedarland, there is no disclosure proving the valuation or verification of all the cobalt that changed hands beyond the gross volume, grade split, and Metal Bulletin pricing.

It’s a black box.

That’s not how it was supposed to work. In multiple filings, Cobalt 27 explicitly promised investors that independent third parties would verify each acquisition before it was finalized. These firms were supposed to inspect the physical cobalt in person, confirm warehouse records, and provide annual audits to verify the company’s holdings.

Which brings us back to the cobalt heist.

In January 2018, Bloomberg reported that Anthony Milewski arranged a tour in Rotterdam to show Cobalt 27’s backers—the “bankers”—the physical cobalt drums, and reassure them “their stash was in safe hands.”27

But if independent verifications existed—real third party audits confirming the trades and inventory—why would those bankers need a tour?

Cobalt: Toxic, Pricey, and Hard to Move

Dealing with raw cobalt is as complex as dealing in raw diamonds.

Cobalt is not a standardized commodity. It comes in multiple forms—hydroxide, ingots, briquettes, and powder—each with its own grades, brands, and industrial applications. Pricing is typically benchmarked to indexes like the Metal Bulletin (now Fastmarkets), but those quotes are high-water marks. Real-world cobalt often trades at a discount, sometimes 20% or more, depending on bulk volume, form, and counterparty.

Physical delivery of cobalt is anything but straightforward. Under U.S. law, cobalt is classified as a Class 9 hazardous material, triggering strict rules around labeling, documentation, packaging, and secure freight handling. Globally, it’s designated toxic under the Harmonized System and must be stored under industrial conditions.

Beyond storage, there’s regulation. Exporting or reselling cobalt often requires specialized permits and licenses. Depending on the jurisdiction, these may include hazardous goods certifications, export control approvals, customs declarations, and anti-diversion protocols. That’s before even considering financial requirements—like trade credit lines, freight insurance, bonded warehousing, and hazmat compliance experts.

In short, for most investors, bartering cobalt for stock isn’t just unusual—it’s operationally implausible.

Investors Couldn’t Afford to Barter Cobalt

Let’s assume, for a moment, that the cobalt-for-stock barter scheme Cobalt 27 offered to U.S. investors was open to the public—you, me, anyone.

In June 2017, if you wanted to buy 135 MT of high-grade raw cobalt and barter it to Cobalt 27, you’d have to pay roughly $11.5 million at prevailing market rates for the cobalt. Then you’d need to take possession, ship it, import it to the U.S., pay duties, insure it, rent industrial warehouse space, and store it as a hazardous commodity. Add another $2.5 million, and your all-in cost approaches $14 million.

But Cobalt 27 wasn’t offering shares based on your cost basis. It was pegging its barter rate to cobalt spot prices in June 2017, offering you the same $11.5 million you paid to buy your cobalt. Since your total costs were $14 million, you’d be facing a loss of 18% or more.

No retail investor could take that deal.

So who were the mysterious counterparties willing to do it anyway?

And how was it profitable for them, but not for you or anyone else?

New Car or Used Car?

Another curious feature of all three prospectuses is the meticulous care taken to omit any detail about the age of the cobalt acquired under the cobalt contracts. The entire topic was ghosted, as if it were irrelevant to investors.

But what if that omission was the point? What if the one thing they didn’t want you to know was the very thing you, as an investor, most needed to?

Let’s put it this way: you walk into a dealership to buy a car. What’s the first thing you ask? “What year is it?” Everyone the world over understands why. The year tells you something important about value.

The filings, however, gave the impression that Cobalt 27 was striking real-time cobalt deals. That was reinforced by repeated references to current Metal Bulletin prices and by risk disclosures focused on supply chain disruption and geopolitical tensions—risks that were only relevant if cobalt was being newly sourced from, say, the DRC or from Mechel, Vladimir Iorich’s former Russian metals company.

Nowhere did the filings clarify whether the cobalt was newly acquired or years old. That omission leaves a central question: were investors buying into a company acquiring new cobalt priced at market on the day of the IPO closing (as could be inferred)—or were those investors paying today’s price for yesterday’s metal?

Put differently, was Cobalt 27 buying $171.8 million worth of new cars—or pre-owned ones?

Or worse—were the cars already sitting in the founders’ garages?

Podcastland

Blueprinted in 2015?

In its retrospective, Shanghai’s Guotai Junan had called Cobalt 27 “a pre-scripted capital game” (一场事先张扬的资本局).28 The script, they implied, had been written well in advance.

Pala was the lead actor. And Cobalt 27? The “white glove” for Pala. Canada was merely the film location.

If that’s true, then Cobalt 27 was a long-planned rollout.

But nothing in Sedarland helps an investor see that. The filings don’t explain how a pre-scripted game got near public markets, let alone retail investors.

For that, we have to leave Sedarland behind and head to Podcastland, where disclosure is looser, and now and then, the truth slips out.

In interviews, three of its founders—Beck, Milewski, and Cochrane—described Cobalt 27 as having been at least two years in the making.

Anthony Milewski said that the company began as a portfolio project inside Pala Investments in 201529 and was later “spun-out.”30 Spin-outs usually involve assets. So what exactly was “spun out”? According to Sedarland, Arak got nothing from Pala.

As noted earlier, in two interviews Justin Cochrane stated that in December 2015, he began “putting the pieces together for Cobalt 27”, after leaving another role.31 If it was being developed inside Pala in 2015, then by his own account, Cochrane was working for, with, or at Pala.

That detail did not appear in Sedarland.

Michael Beck, who described himself as the “long-time partner of Stephen Dattels,”32 said they began looking at cobalt in March 2016,33 although in two other interviews, including an earlier one lauding his Uramin deal, he said he and Dattels began focusing on battery materials in 2015.34

In a 2019 podcast, Beck was even more direct. He said:

“In the case of Cobalt 27 … we had to create [it], and it wasn’t just me. It was Anthony Milewski and the Pala Guys.”35

That, for sure, was left out of Sedarland.

So while Cobalt 27 appeared to be a fresh play in 2017, it had been incubated quietly in Zug, Switzerland, as early as 2015—if not 2014—by Iorich, Milewski, Cochrane, Beck, and, by implication, Dattels.

More to the point: was the cobalt stockpiling scripted years in advance too? And were the founders the ones doing the stockpiling as early as 2015, if not 2014—long before retail investors had ever heard of Cobalt 27?

That too is hinted at in Podcastland.

After saying he joined in December 2015, Cochrane explained, “we built the physical position.”36

Beck was more specific. He said they had gone “out the prior 18 months” and “bought every scrap of cobalt they could find.”37 He didn’t clarify who “they” were, but having said he co-created Cobalt 27 with Pala, the implication was that “they” meant him and the Pala team.

Milewski told the German partner of prolific stock promoter Björn Paffrath that the cobalt acquisitions “took a couple of years to put together,”38 placing their start around 2015. He gave Bloomberg a similar timeline, stating that purchases began in 2015 while he was still at Pala.39

In their report on Cobalt 27, Guotai Junan charted cobalt prices, showing they remained flat or declined between 2009 and 2015. But around the time the founders claimed they began acquiring cobalt from global markets, prices began climbing sharply—eventually peaking in March 2018.

The cobalt price surge coincided with the period Guotai Junan identified as the entry of speculative capital led by Pala Investments, marked in their report by the blue-shaded box above: “以Pala投资为首的投机资金进入, 钴价大幅上涨”.40

Questions and No Answers

If this timeline holds, the implications are stark. It suggests that some founders cornered cobalt during a downturn, then triggered a rally through accumulation. That inflated price became the foundation for the IPO’s $9 share price—up from just $0.14 in the private round. And at that price, they bartered or sold their own cobalt back into the public vehicle.

But if they had quietly cornered the market in 2015, why did they need to keep buying in 2017? And more importantly—where was that cobalt? Who was really behind each of the cobalt deals Cobalt 27 executed? What had those counterparties originally paid?

If it was 2015 inventory, why wasn’t that disclosed? Why present it as a bold market buy rather than what it may have been—a quiet markup?

As with much of Cobalt 27, the story frays at the edges. If we take Beck at his word—and “they” really did buy every scrap of cobalt they could find—then there shouldn’t have been much left to acquire in the world. So whose cobalt was Cobalt 27 buying, if not their own?

Back to Sedarland

Which brings us back to the cobalt heist story.

When Cobalt 27 brought bankers and journalists to its Rotterdam warehouses to show them the physical cobalt they had acquired under the cobalt contracts, Bloomberg reporters took photos.

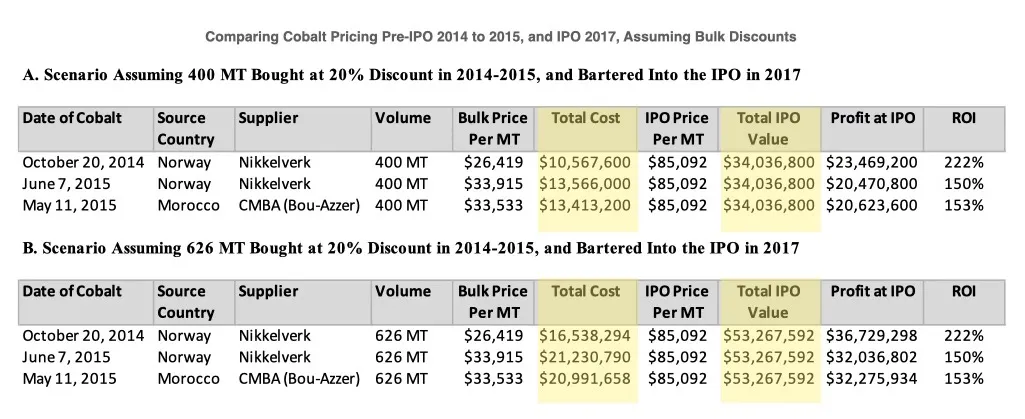

Zoomed in, the photographs, below, revealed cobalt drums from Morocco and Norway stamped “2014” and “2015”—two to three years before the IPO. That detail matched the founders’ admissions in Podcastland and reinforced Guotai Junan’s timing of early accumulation.

Closer Look at the Math

If we put it all together—Sedarland omissions and Podcastland admissions—we begin to see a new picture. The IPO’s barter-for-shares and cobalt shopping spree meant investors were buying pre-owned cars at brand-new prices. And some insiders? They were the ones who had parked those cars in their garages years earlier, before offloading them into the IPO at showroom value.

That’s why the scheme worked for counterparties holding old metal bought at depressed prices—but not for retail investors.

The warehouse photos hint at the scale: rows of blue and red cobalt drums stacked to the ceiling stamped “20/10/14,” “05/11/15,” “11/06/15,” “06/07/15.”

None of this is in the prospectuses. Neither is the profit they stood to make.

Run the numbers, and the windfall becomes tangible. Hypothetically, if someone bought 626 MT of Norwegian cobalt in 2014 at bulk-discounted rates, the cost would’ve been around $16.5 million based on publicly available data.

By 2017, if that same stockpile was bartered into the IPO, it would have yielded $53.3 million—a $36.7 million gain.

So, this much, at least, appears clear: some of the founders acquired cobalt at 2014–2015 prices, discounted further for bulk, warehoused it, then bartered or sold it into the IPO at 2017 peak valuations. They monetized old inventory at new prices—using a valuation they helped create.

They profited twice: a 6,328% gain on their $0.14 shares, and a threefold markup on warehoused metal. A double-dip windfall.

And ordinary investors like you? Many were exited at a loss by a Russian oligarch and left holding the bag.

And Sedarland? What else is there to conclude, except that for some, disclosure is optional and profits are mandatory.

Coming Next: Part 4—Diving into the Cobalt Trades

We began with a mystery: how did an 80-year-old Oregon doctor end up supplying enough raw cobalt to fill three Boeing 737 cargo planes for Cobalt 27—as if it were just another house call?

And how did a shell company—formed days before a $44 million deal—move a cobalt load weighing as much as 112 African elephants from the same address as Voyager Digital? And if the company didn’t exist weeks or months earlier, where did the cobalt come from?

In Part 4, the paper trail loops through recurring ZIP codes, familiar names, and even a fake bank routing number.

Next: we follow the cobalt and see where the trail leads.

Footnotes

- Guojin Securities Co. Ltd., Cobalt 27的前世今生, industry专题报告, December 11, 2017.

- Guotai Junan Securities (国泰君安证券), Cobalt 27,一场事先张扬的‘钴价’资本局, 微信公众号, December 19, 2019.

- Guojin Securities, Cobalt 27的前世今生.

- Guotai Junan, Cobalt 27,一场事先张扬的‘钴价’资本局.

- Ibid.

- Silver Bullion TV Channel, “Electric Vehicle Revolution: Game Over for Petrol/Diesel Vehicles,” December 16, 2018.

- Guojin Securities, Cobalt 27的前世今生.

- Journalist Emmanuel Fansten called it “une énorme escroquerie” in Affaire Areva-Uramin: Révélations sur un scandale d’État?, broadcast on CNEWS, February 10, 2016. Libération described it as “une gigantesque escroquerie,” as reported by Radio France Internationale on February 11, 2016, in Nucléaire: Areva aurait menti à l’État sur la valeur d’Uramin. Patrick Pesnot also referred to it as “une escroquerie” in Areva et le scandale Uramin, Rendez-vous avec Mr. X, Radio France, January 10, 2015.

- Céline Hervieux-Payette, Debates of the Senate (Hansard), 42nd Parliament, 1st Session, no. 25 (April 12, 2016), 1420. https://sencanada.ca/en/content/sen/chamber/421/debates/025db_2016-04-12-e#23.

- Based on patterns in other deals, such as Voyager Digital and Pasofino Gold Limited, some of these investors tend to move in lockstep, taking identical stakes. In Cobalt 27’s case, some appear to have acquired identical 6.46% positions in the founder’s private placement (e.g., Pala’s Iorich and Milewski each taking 300,000 units, aligning with NewGen’s 300,000 units).

- Michael Beck confirmed he was a shareholder of Cobalt 27 and involved prior to its public emergence in 2017. See Palisades Gold Radio, “Mike Beck: Cobalt – The Most Supply Constrained Commodity on Earth, By Far,” YouTube video, November 25, 2017; and see Silver Bullion TV, “Mike Beck – Electric Vehicle Revolution: Game Over for Petrol/Diesel Vehicles,” YouTube video, December 16, 2018.

- Jeanne Usonis typically participates in private placements alongside Beck.

- Seifert was possibly an investor both due to his role as a co-founder of Voyager Digital and reports that he accompanied Beck to every meeting under the Regent Advisors LLC banner.

- Anthony Milewski explicitly identified himself as the founder of Cobalt 27. See Bloomberg News, Grand Theft Cobalt: Rotterdam, December 27, 2018. Prospectus filings also confirm that he held pre-IPO shares.

- Mike Beck stated that “Pala Guys,” along with himself and Anthony Milewski, were behind Cobalt 27. See Palisades Gold Radio, Mike Beck: Highly Successful Resource Investor Shares His Latest Big Bet in Nickel, YouTube video, October 9, 2019.

- Anthony Milewski stated that no one noticed Pala Investments “participated in every single financing.” See Creative Return, “The Untold Story with Anthony Milewski,” podcast audio, February 19, 2020. After the IPO closed, Pala disclosed that it had held 300,000 pre-IPO shares, which it could only have acquired during the March private placement. This disclosure was non-transparent, requiring calculations of share data to determine Pala’s original holdings.

- After the IPO closed, Green Energy Fund disclosed holding warrants, which it could only have acquired during the March 2017 private placement as a founder, or earlier from an unidentified shell shareholder.

- The governance dysfunction visible at inception would appear systemic in hindsight, especially when viewed through the lens of Nickel 28. This can arise when those in charge aren’t always fully steering the company. A good comparable is BetterLife Pharma Inc., a Vancouver issuer tied to some of the same individuals in Cobalt 27. While Cobalt 27 executives had no involvement in BetterLife, BetterLife did a pivot to a Covid-19 play, oddly triggered by an email Anthony Milewski sent to Michael Beck and Jeanne Usonis at Regent Advisors LLC, referencing a Stan Bharti Covid-19 play.

- Silver Bullion TV Channel, “Electric Vehicle Revolution: Game Over for Petrol/Diesel Vehicles,” December 16, 2018.

- Ibid.

- SmallCapPower, “Cobalt 27 Capital President: We Have the Biggest Cobalt Supply Outside China,” December 12, 2017.

- Pala’s founder shares are only discoverable through post-IPO inference. In a filing made after the IPO, Pala disclosed that, prior to the 20-for-1 share consolidation (approved by board resolution on May 23), it held 1,800,000 shares—equivalent to 300,000 units in the March 2017 placement.

- Creative Return Podcast, “The Untold Story with Anthony Milewski,” February 19, 2020, https://www.creativereturn.ca/post/anthony-milewski-1.

- SmallCapPower, “Cobalt 27 Capital President.”

- The Northern Miner, “Cobalt 27’s Anthony Milewski Discusses Vale Transaction, Cobalt Outlook,” July 3, 2018, https://www.northernminer.com/news/cobalt27s-anthony-milewski-discusses-vale-transaction-cobalt-outlook/1003797493.

- Palisades Gold Radio, “Mike Beck: Cobalt – The Most Supply Constrained Commodity on Earth, By Far,” video, November 25, 2017.

- Bloomberg News, “Grand Theft Cobalt: Rotterdam,” December 27, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2018-12-27/thieves-pull-off-audacious-cobalt-heists-at-europe-s-largest-port.

- Guotai Junan, Cobalt 27,一场事先张扬的‘钴价’资本局.

- Bloomberg News, “Grand Theft Cobalt: Rotterdam.”

- Creative Return Podcast, The Untold Story with Anthony Milewski.

- SmallCapPower, “Cobalt 27 Capital President”; Creative Return Podcast, “Capitalizing on Carbon Credits with Justin Cochrane,” May 28, 2022, https://www.creativereturn.ca/post/justin-cochrane.

- Palisades Gold Radio, “Mike Beck: Keynote – Parabolic Growth for Electric Vehicles Is Now Beginning,” June 8, 2019.

- Palisades Gold Radio, “Mike Beck: Nickel, Cobalt and Lithium to Benefit from Generational Demand Shift in Commodities,” November 21, 2017.

- Palisades Gold Radio, “Mike Beck: Uranium Superstar Goes All In on Battery Metals,” October 26, 2017.

- Palisades Gold Radio, “Mike Beck: Highly Successful Investor Shares His Latest Big Bet in Nickel,” October 9, 2019.

- SmallCapPower, “Cobalt 27 Capital President.”

- Palisades Gold Radio, “Nickel, Cobalt and Lithium.”

- Swiss Resource Capital AG, Cobalt 27 Capital: Acquiring Physical Cobalt, Streams & Royalties, video, December 14, 2017.

- Bloomberg News, “Grand Theft Cobalt: Rotterdam.”

- Guotai Junan, Cobalt 27,一场事先张扬的‘钴价’资本局.