Foreign actors attacking US capital markets

The Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC“) has filed a complaint against several Vancouver individuals involved in the microcap space, calling them “foreign actors” and accusing them of attacking the US capital markets and US investors using various alleged securities fraud schemes. The SEC says that over US$1 billion in illegal stock sales occurred under the control of a handful of Vancouver individuals in less than a decade.

It’s believed to be the first time that the SEC has used such language and referred to Vancouver market participants as foreign actors attacking the US financial markets.

This case is also important because of the June 3, 2021,”Memorandum on Establishing the Fight Against Corruption as a Core US National Security Interest” issued by US President Biden, pursuant to which he stated, inter alia, that professional service providers enable money laundering and support corruption, and threaten the national security of the US, threaten democracy and harm the rule of law. Among the resultant harms he listed, was market distortion.

So while on its surface, this SEC case is about alleged pump and dump fraud schemes allegedly perpetrated by alleged secret control persons in the corporate law sense, it is also about the take down by US law enforcement of professional service providers, more particularly “company service providers”.

Connected cases tied to Vancouver

This SEC complaint ties into earlier SEC enforcement actions against other people in the capital markets, some but not all of which are connected to Vancouver (see, for example, SEC v. Carrillo et. al., SEC v. Basic et al. and SEC v. Knox).

The Canadian defendants in this case are Frederick Sharp, Zhiying Chen, Courtney Kelln, Mike Veldhuis, Paul Sexton, Jackson Friesen, Graham Taylor and Avtar Dhillon. The microcaps whose shares were manipulated, says the SEC, include a Vancouver Bitcoin company called Evolution Blockchain Group Inc., OncoSec Medical Incorporated, Arch Therapeutics Inc. and Vitality Biopharma Inc. Zhiying Chen is a/k/a Yvonne Gasarch in Canada; Zhiying Chen in China.

The SEC is seeking a permanent injunction against the defendants, enjoining them from violating the Securities Act and Securities Exchange Act, as well as other relief including disgorgement.

Company service providers

The SEC alleges that Sharp, Chen and Kelln worked at one company (“Sharp Co.”) which provided corporate registry services (e.g., known as “company services providers” under the FATF Recommendations as part of DNFBPs).

“Company services providers” provide services that involve incorporating and maintaining private companies domestically, and arranging for such services offshore with other company services providers in offshore jurisdictions. Company service providers, materially, control corporate records and they not only create the paperwork to evidence the officers and directors of private companies, they control its anonymity (or not).

The FATF Recommendations require that such persons be registered under AML law but Canada decided to exempt the regulation of company service providers under the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) Terrorist Financing Act because they took the position that company service providers were not material in the money laundering ecosystem in Canada.

Threema and secret communications; secret control persons; secret promoters

The SEC alleges that Sharp Co. employed the use of cellular phones it called “xPhones”, which were cellular devices which operated on an encrypted network. That network appears to be Threema, which promises a guarantee of encryption of messaging. Sharp Co. also, the SEC alleges, acted as what appears to be an unregistered money services business, exchanging funds and moving funds around for clients.

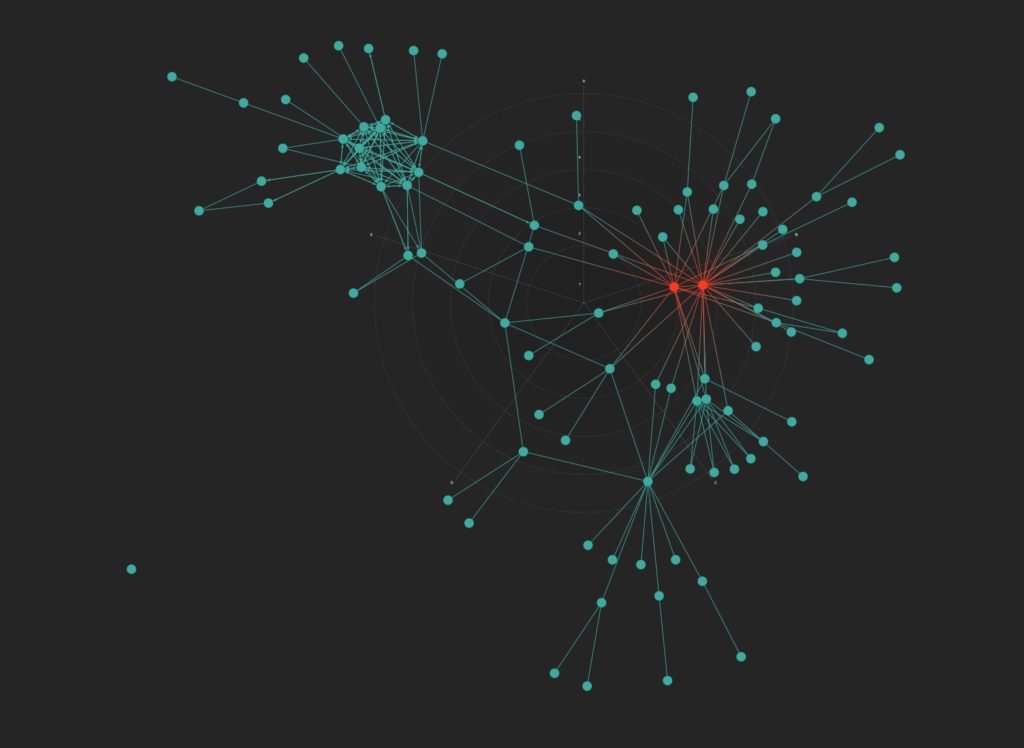

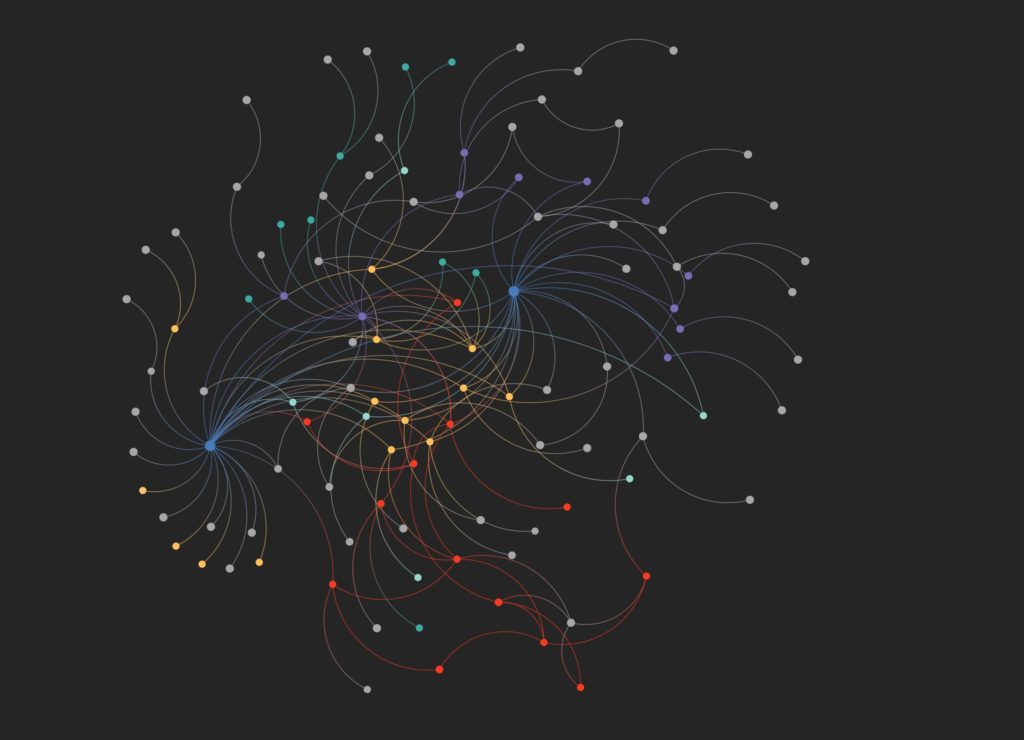

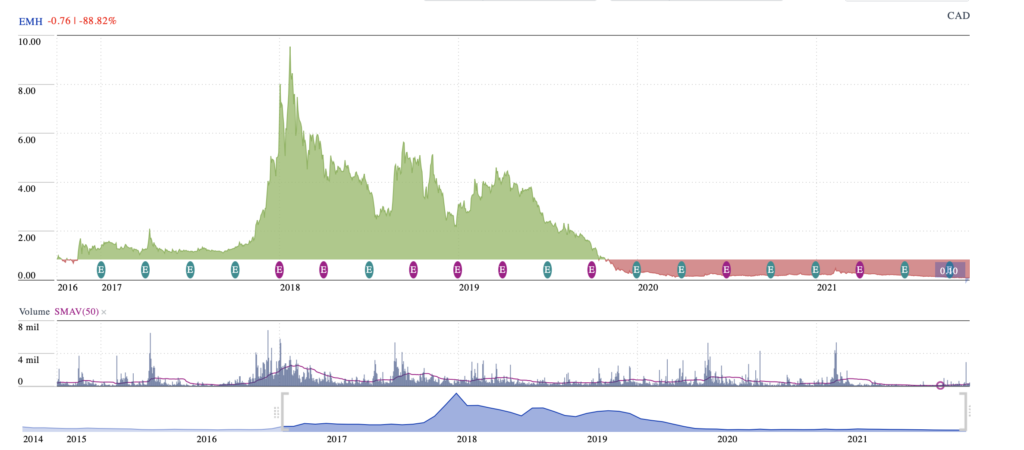

The pleadings say that Dhillon is a business associate of Sharp and is described as a super control person and an insider, who appears to have controlled the control persons. According to an Affidavit filed by the FBI, Dhillon directs another little issuer named Emerald Health Therapeutics based in Vancouver, Canada, listed in the US on the OTCBB. It had days where millions of shares were sold in a period of a few months in late 2017, as depicted in the graph, below. It is not named as part of the SEC complaint as an issuer whose securities were allegedly manipulated.

The SEC says that Dhillon used a paid promoter named William Kaitz. He allegedly promoted the stock of the issuers named in the complaint that the control persons allegedly dumped after such stock had been pumped up to artificially high prices. Kaitz is also alleged to have concealed the identity of the entity that paid for the stock pumping services. Sharp Co. allegedly provided Kaitz with one of the xPhones for what they believed would be secret communications. According to securities law disclosures filed for investors, Dhillon states that he was formerly with a Canadian entity named Lumira Capital Corp. and another named BC Advantage Funds (VCC) Ltd. Both are VC funds in Vancouver, Canada and the latter appears to have gone bust and self-liquidated its assets and was wound up.

James Bond culture

Some of the defendants appear to have believed they were running covert ops, and were akin to secret agents.

The leader of Sharp Co., Fred Sharp, used the code name “Bond”, as in 007 for himself, and described his firm’s services as comprehensive and which included payment processing, loans, private placements and “keeping clients out of jail.” He appears to have written a book of fiction in 2003 and has an IMDb profile. The Facebook page of one of his children has “007” as part of the profile name.

Sharp’s company services provider entity was called Corporate House, operated out of Vancouver. It was one of the largest clients from Canada of Mossack Fonseca, the law firm in Panama that melted down after the Panama Papers, and in fact Sharp ran a Canadian office of Mossack Fonseca in Vancouver.

The SEC alleges that Sharp found front people and front companies for the scheme. One such front person was his wife’s tennis coach in Vancouver.

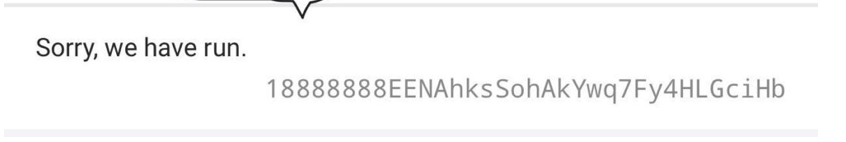

Along the James Bond theme, the SEC says that Sharp set up a secret accounting system called “Q”, allegedly to track the proceeds from the illegal sales of securities. Q also allegedly tracked the fees and commissions payable to Sharp Co. for alleged obfuscation and other professional facilitator services. The encrypted communications and Q were hosted on servers in Curaçao because Sharp believed that Curaçao was beyond the reach of US law enforcement. He was wrong – pursuant to an MLAT, the FBI obtained mirrored copies of Q and the xPhone communications from Curaçao.

The SEC alleges that from Vancouver, Sharp’s associate Kelln, hired a number of lawyers – not of the issuers but of the Vancouver nominee shareholders associated with Dhillon and Sharp, and the SEC says they wrote false opinion letters opining that shares of the microcap issuers were unrestricted, when they were not. The SEC may reveal in due course, who wrote the false opinion letters but thus far they have not.

Parallel criminal filings

In parallel proceedings, the US Attorney for the District of Massachusetts announced criminal charges against Sharp, Kelln, Veldhuis and Dhillon (and one other) for conspiracy to commit securities fraud and securities fraud. The FBI Affidavit in support for Sharp et. al. is here. When the case was unsealed, arrest warrants were issued for Sharp, Veldhuis and Kelln. A separate criminal complaint was issued against Dhillon for securities fraud, conspiracy to commit securities fraud and for obstruction for lying under oath on a number of occasions to the SEC during its investigation. A warrant was issued for Dhillon’s arrest as well. Although Dhillon resides in California, he is from British Columbia.

The Dhillon criminal complaint provides a more fulsome picture of the allegations from the microcap issuer perspective. The US Government alleges that Dhillon and his lawyer deliberately hid certain shareholdings of microcap companies he owned using two shell companies. One shell was called “Walk on Water”, perhaps because Dhillon felt he walked on water and was untouchable. Dhillon and his lawyer are alleged to have conspired to defraud several investors (shareholders) and to have obtained money from them based on false representations connected to companies they were raising funds for. Dhillon allegedly sold shares he secretly owned that were held in the names of nominee shareholders (which was not disclosed) after promotional schemes increased the price, artificially, of those shares.

Dhillon, the US government states, had in particular, corporate ties to his fellow co-accused Sharp and Veldhuis through the use of nominees, and also to his fellow co-charged, Friesen, Taylor and Sexton, and as between them, they allegedly transferred shares to nominee entities or nominee persons, or instructed others to do so.

A Vancouver Blockchain company

One of the issuers identified in the SEC proceeding is a Vancouver Bitcoin company called Evolution Blockchain Group (formerly Garmatex Holdings Ltd.). It did a pivot from allegedly making bras and allegedly being a supplier of fabric to the global brand ASICS, to become a Blockchain company during the ICO hype. It is headquartered, and during the relevant time operated from Vancouver although incorporated in Nevada. Its president is or was a geologist in Ontario named Lawrence Stephenson. Although allegedly supplying fabric for bras and ASICS, no material contract was filed on Edgar or Sedar with ASICS.

According to its filings on Edgar, it bought a Bitcoin gambling payments website and Bitcoin gambling software from Canada, from 10604496 Canada Inc., whose shareholders are disclosed on Edgar as including Dominic Dos Santos, Bradley Rowe, Naeem Kassam, Randy Bunka, Dean Stambolich, Tony Marziliano, Richard Lonsdale-Hands, Crystal Casey and Junior Ofori. The assets were purchased in April 2018, although the company was only incorporated a few months earlier.

Drive Coin ICO

Evolution Blockchain also launched an ICO from Vancouver called “Drive Coin” (as in driving a vehicle), and provided online crypto lending, according to its website.

A boiler room in Colombia cold calling to sell stock

According to the SEC, at the beginning of March 2017, one of the secret control persons of Evolution Blockchain paid a boiler room operator in Medellin, Colombia, to call US investors to promote the stock of Evolution Blockchain. They also launched an email campaign to promote the stock and then hired a promoter in Canada to pump the stock.

When the stock was shooting up, the SEC alleges that the issuer issued a press release stating that it was unaware of anything that could account for the increase in its market activity. That pump and dump, the SEC says, resulted in US$7 million in illicit proceeds just for the one secret control person but that same person collected US$75 million from the fraudulent trades of securities over the course of nine years, says the SEC. The SEC does not state who published the press release on Sedar.

Another stock that was allegedly sold at the Colombian boiler room was PureSnax International Inc., now IQST, which is an issuer in Florida that states that it allegedly sells FinTech, Blockchain, and electric vehicle services, as well as operates a digital currency exchange. Previously, it allegedly manufactured healthy snacks according to its Edgar filings with one or more Canadian, but reported having no employees or facilities. The other is Oroplata Resources Inc., now American Battery Metals Corporation (ABML), a lithium battery issuer.

The documentary (clips below) by 60 Minutes Australia shows the busting of a boiler room that sold fake securities listed in the US to victims in several countries. In the documentary, the boiler room cold callers blame victims of securities fraud for the thefts, calling them “stupid.”

This is called neutralizing – neutralizing theory is used by scholars to explain how securities fraud and other financial crime criminals rationalize their conduct by blaming others for criminal acts they commit. For example, both Charles Ponzi and Bernie Madoff neutralized to law enforcement (and in their own minds) to deflect blame to others for their schemes.

But it isn’t what the boiler room promoters say in the 60 Minutes documentary, so much as their attitude towards the harmed investors that is different.

Watch this clip below from 1:44 to 1:50.

And then watch this part below from 14:54 to 15:40.

In the documentary, one of the interviewees characterizes boiler room securities fraud activities as transnational organized crime, and says that whistleblowers of securities fraud have been killed.

That is true – over ten years ago, David Bains, who was a reporter in Vancouver, reported about a British Columbia issuer listed on the OTCBB, run and promoted by organized crime, where, he reported, five people were killed in Vancouver by organized crime for reporting to regulators that the issuer was engaged in a pump and dump scheme. Fast forward to today and one of those organized crime figures is active in the Vancouver microcap space as an executive of at least two issuers, according to Sedar filings.

Fake expertise to pump the stock

Lawyers at the American Bar Association (“ABA“) wrote an excellent law review article looking at penny stock fraud perpetrated against Americans, including from foreign issuers (most of which are in Canada) and, with respect to the creation of fake documents similar to the allegations in this SEC case, the ABA wrote that professional facilitators who work in the microcap pump and dump space who prepare documents for issuers that involve misrepresentations, do so “fully aware of the corporate fiction they are creating”.

The ABA went on to describe a troubling practice of fraudsters who use the names of people who are well-educated and with credentials to give themselves credibility and respectability without the knowledge or consent of such persons.

Bitcoin people, particularly, have often used the names and likenesses of lawyers, law firms, and large global advisory firms without the knowledge or consent of the persons or the firms.

Both the SEC and the OSC have taken regulatory action against Canadian capital markets participants who have expropriated the names or likenesses of individuals without their consent or knowledge on the basis that it is a type of fraud on the market.

Supporting the ABA finding that the fraudulent use of someone’s name happens frequently, a recent case brought to our attention involved a case whereby an issuer in Vancouver took the names of experts of another company and without the knowledge or consent of the individuals involved, posted their likenesses and names on the issuer’s website, alleging they were consultants and/or advisors of the issuer (which was not true) and raised money from US investors relying upon that misrepresentation.

A few years ago, a Bitcoin issuer in Vancouver used the logo of a US federal law enforcement agency on its website and in its pitch deck, without the knowledge or consent of the US federal law enforcement agency, to raise money from investors and only ceased to do so after the US federal agency communicated with the issuer to request they remove the US government logo.

And just yesterday, a Vancouver microcap issuer listed on the OTCBB, whose stock is being promoted via email newsletters as a company that “literally could SAVE LIVES!” by a promoter put the logos of the US Special Operations Command, NATO, the US Department of Defense and the US Marines on its website and in its pitch deck to investors, alleging that each of those agencies were tied to the issuer. According to its Sedar filings, the issuer does not have one direct contract with any US military agency or with NATO.

SEC whistleblower program

With respect to the Sharp and Dhillon case, if there is a silver lining, it may be that some parts of this SEC and DOJ action arose, in part, because of a filing by an American pursuant to the SEC whistleblower program in the US, which speaks to the effectiveness of the program, as well as the trust that it has among the public in its handling of cases that result in helping to protect the integrity of the US capital markets, and this case may be the catalyst that convinces lawmakers to adopt effective trust-based whistleblower laws in Canada where no one is at risk for being a securities law whistleblower.

If you are interested in other boiler rooms cases connected to Canada, you can read this story here about Canadians who ran a boiler room scheme, whom US law enforcement prosecuted, and also refer to the CFTC and OSC cases against Canadians who ran alleged binary options scams from Israel that used boiler rooms to sell the securities.